توڭلىتىلغان خېمىل ۋە مۇناسىۋەتلىك مېيىنىڭ خۇسۇسىيىتى (HPMC) نىڭ تەسىرى

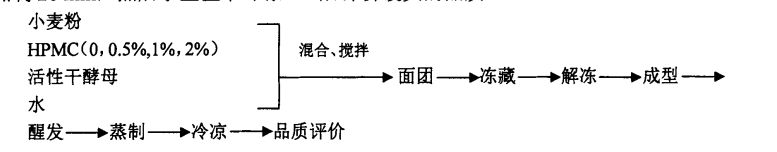

توڭلىتىلغان خېمىرنىڭ بىر تەرەپ قىلىش خۇسۇسىيىتىنى ياخشىلاش, يۇقىرى سۈپەتلىك قۇلايلىق چۈشۈشنىڭ چوڭ تىپتىكى پارلىغۇچىسى بولكىنىڭ ئىپادىسى كەڭلىكىنى مەلۇم قىلىشنىڭ مەلۇم ئەمەلىي ئەھمىيىتى بار. بۇ تەتقىقاتتا, يېڭى تىپتىكى گىدروفىللىق كولوئىز (Hydroypropy Mythylcellulluy, Yang, MC) توڭلىتىلغان خېمىردەك ئىشلىتىلگەن. توڭلىتىلغان خېمىر, پىرسەنت خېمىر ۋە پارنى بىر تەرەپ قىلىش خۇسۇسىيىتىدە% 1,% 1,% 1)% 1,% 1,% 1,% 1)% 1. زاپچاسلارنىڭ قۇرۇلمىسى ۋە خۇسۇسىيىتىگە بولغان تەسىرى (بۇغداي گلۇتېن, بۇغداي كراخمال ۋە ئېچىتقۇچىلىق).

قىزىل تەرەپلىك ۋە سوزۇلغان تەجرىبەنىڭ ئۈلگىسى »نىڭ خېفىلنىڭ ھەرىكەتلەندۈرگۈچ كۈچى ۋە ئۇزۇن يىللىق قىستۇرمىلارنىڭ يۇقىرى كۆتۈرۈلگەنلىكى كۆرسىتىلدى, چېگرىنىڭ ئازابى بىلەن قوشۇلغاندا, توڭلىتىش بىر نەرسە مۇقىم بولدى. ئۇنىڭدىن باشقا, كونترول توپى بىلەن كونكرېت ھاۋا ۋە ئېلاستىك بولغان ئىممۇنىتتۇرۇلغان, توڭلىتىلغان خېمىر بىلەن% 2 HPMC بىلەن 20 كۈن باشلانغاندىن سېلىشتۇرغاندا قاتتىق ئاشتى.

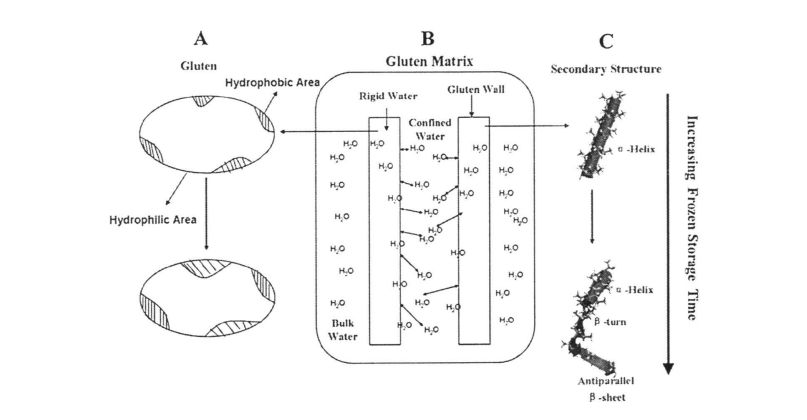

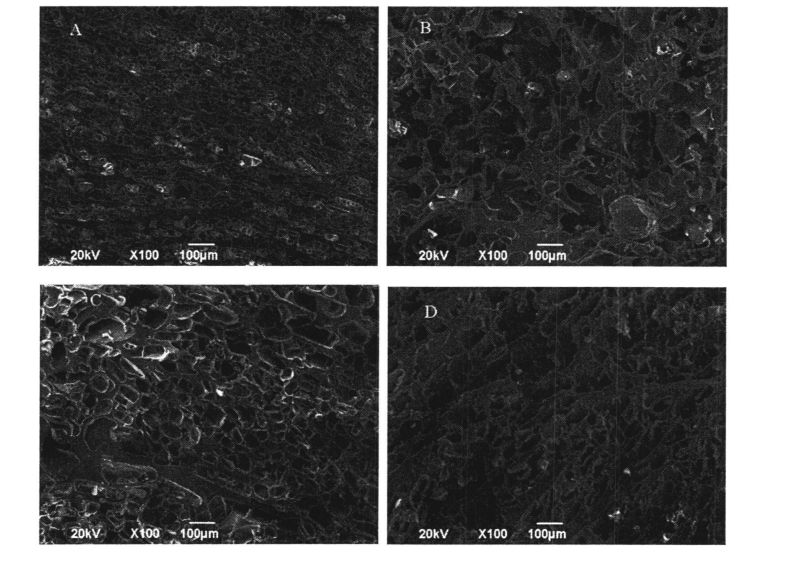

بۇغداي گلۇتان خېمىر تورى قۇرۇلمىسىنىڭ شەكىللىنىشىنىڭ مۇۋاپىق ئاساسى. تەجرىبە بايقىشىچە, مەن قوشۇلغاندىن كېيىن, مەن - IPMC توڭلىتىش جەريانىدا ياڭاق يېتىشمەسلىك يولىنى ئازايتىدۇ ۋە بۇغاق يېغىل چىۋىن ئاجىز ئاقسىللارنى ئازايتىدۇ. بۇنىڭدىن باشقا, تۆۋەن قاتلاملىق يادرو ماگنىتاك رەت قىلىش نەتىجىسىنىڭ سۇ دۆلەت ئۆتۈلۈپ كېتىشى ۋە ئاساسەن سۈزۈكلەشتۈرۈش ۋە قايتا بېسىلۈشنىڭ نەتىجىلىرى ۋە خېمىرنىڭ يېغىشىنىڭ ئۆستۈرۈلىدىغان سۇنىڭ ئۈنۈمىنى بېسىدۇرا بولىدۇ. سايلاشنى سايىلەپ ئېلېكترون MicroSCOPE دا ئوكۇلتورىيە كۆرسەتتى, HPMC نىڭ Gluten تور قۇرۇلمىسىنىڭ مۇقىملىقىنى ساقلىشى مۇمكىنلىكىنى كۆرسىتىپ بېرىدۇ.

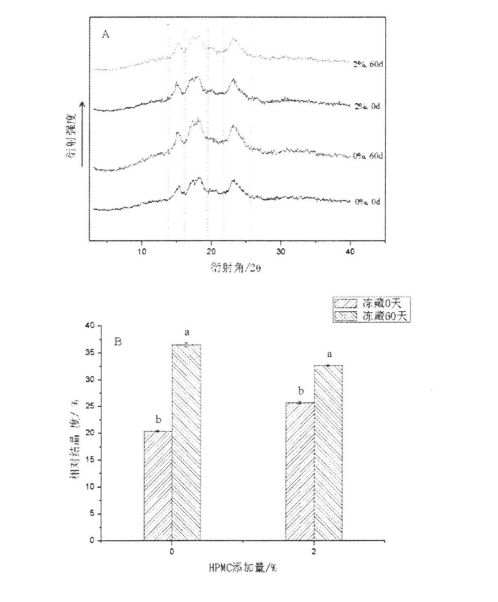

كراخمال بولسا خېمىردىكى ئەڭ كۆپ قۇرۇق ئىش, ئۇنىڭ قۇرۇلمىسىنىڭ ئۆزگىرىشى سۈتتىن ئايرىشنىڭ خاراكتېرى ۋە ئاخىرقى مەھسۇلاتنىڭ سۈپىتىگە بىۋاسىتە تەسىر كۆرسىتىدۇ. X. X نەينىڭ مىللىتىيىسىنىڭ نەتىجىسى ۋە DSC ستاتىستىكا كرېستنىڭ نىسپىي خرۇستاللىقى ۋە قىستىتا ئىس-تۈتەكلىك دورا مىقدارىنىڭ كۆپەيتىلگەن نۇسخىسى. توڭلىتىش ۋاقتىنى ئۇزارتىش بىلەن, HPMC بۇنىڭدىن Orekch نىڭ يوشۇرۇن كۈچى تەدرىجىي تۆۋەنلەپ, گراكتەك ھايۋاناتلاشتۇرۇش كۈچى (مۇشۇنداق تارىيىدىغان ئەڭ مۇلىنىدۇ, چىداملىق قىممەت, چىداملىق قىممەت ۋە قايتا كۆرۈش قىممىتى تۆۋەنلىدى ساقلاش ۋاقتى كەلگەندە, كونترول گۇرۇپپىغا سېلىشتۇرغاندا, HPMC دىن ئۆسۈشىگە سېلىشتۇرغاندا, Collecch Crychstast قۇرۇلمىسى ۋە زالىملاشتۇرۇش مۈلكىسىنىڭ ئۆزگىرىشى بار.

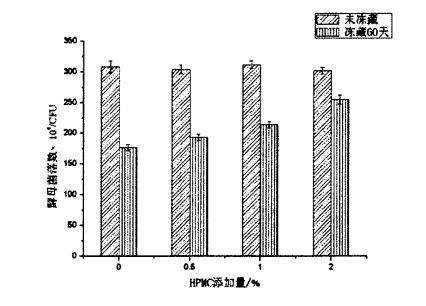

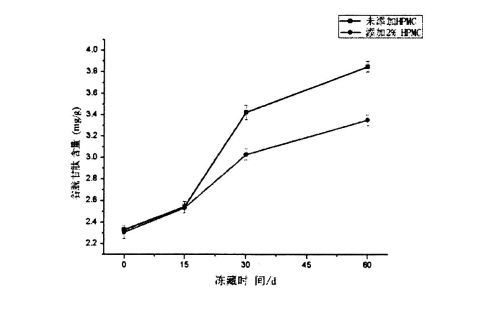

شەرەپلىك تەبىئىي گاز ئىشلەپچىقىرىش پائالىيىتى ۋەقەلەنگەن ئۇننىڭ سۈپىتىگە ئىنتايىن مۇھىم تەسىر كۆرسەتتى. سىناق قىلىش ئارقىلىق, كونترول گۇرۇپپىغا سېلىشتۇرغاندا, Hpmc نىڭ راز-ياراغ پائالىيىتىنى تېخىمۇ قوغلاپ چىقىرىش, HPMC نىڭ ئىشلىتىلىشى قوشۇلغان.

نەتىجىدە HPMC نىڭ توڭلىتىلغان خان جەمەتى, بىر تەرەپ قىلغۇچ خان جەمەتىنى ۋە ھورنىڭ سۈپىتىنى ئۆستۈرگەنلىكىنى كۆرسىتىپ بېرىدۇ.

ئاچقۇچلۇق سۆزلەر: ھور: نان توڭلىتىلغان خېمىر hydroxypropyl Mythylullouse; بۇغداي گلۇتېن; بۇغداي چولپانلار ئېچىتقۇ.

جەدۋەلنىڭ مەزمۇنى

Chapter 1 Preface ................................................................................................................................. 1

1.1 ئائىلە ۋە چەتئەلدىكى تەتقىقاتنىڭ ھازىرقى ھالىتى ........................................................... l

1.1.1 Mansuiqi نى تونۇشتۇرۇش

1.1.2 ھورلانغان پار-يۇندىلارنىڭ تەتقىقات ئەھۋالى ................................................................. . ............ 1

1.1.3 توڭلىتىلغان خېمىر تونۇشتۇرۇش .................................................................................................................... 2

1.1.4 توڭلىتىلغان خېمىرنىڭ مەسىلىسى ۋە قىيىنچىلىقى .............................................................................. .3

1.1.5 توڭلىتىلغان خېمىرنىڭ تەتقىقاتى ................................................. ...............................................

1.1.6 توڭلىتىلغان خېمىر سۈپىتىنى ياخشىلاشتا گىدروكولوزىتلىرىنى قوللىنىڭ ......................5

1.1.7 mydroxyprapyl mythyl melloupy (Hydroyspropyl Mythyl Smouluel, i-ipmc) .......... 5

112 Purpose and Significance of the Study ................................................................................ 6

1.3 The main content of the study ...................................................................................................7

2-باب توڭلىتىلغان خېمىرنىڭ بىر تەرەپ قىلىش خاسلىقى ۋە ھورلانغان بولكىنىڭ سۈپىتىنىڭ سۈپىتى بىلەن ئۇچرىشىشنىڭ تەسىرى ئاستىدا, نانقىچە بولكا سۈپىتى.

2.1 Introduction ...................................................................................................................................... 8

2.2 Experimental materials and methods ........................................................................................8

2.2.1 Experimental materials ................................................................................................................8

2.2.2 Experimental Instruments and Equipment .............................................................................8

2.2.3 Experimental methods ................................................................................................................ 9

2.3 تەجرىبە نەتىجىسى ۋە مۇلاھىزە ..................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 11

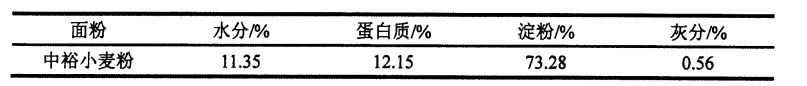

2.3.1 بۇغداي ئۇننىڭ ئاساسىي زاپچاسلىرى كۆرسەتكۈچى ......................................................................................1

2.3.2 HPMC نىڭ خېمىردىن ئايرىلغان دېھقانچىلىق دورىلىرىنىڭ تەسىرىدىن باشقا HPMC نىڭ تەسىرى ........................11

2.3.3 HPMC نىڭ ھەشەمەتلىك زەھىرىدىن قوشۇلۇش خۇسۇسىيىتىدىن باشقا, .................................... 12

2.3.4 HPMC قوشۇشنىڭ ئۈنۈمى ۋە خېمىرنىڭ رولۇت خۇلاسىسى. ................................. .

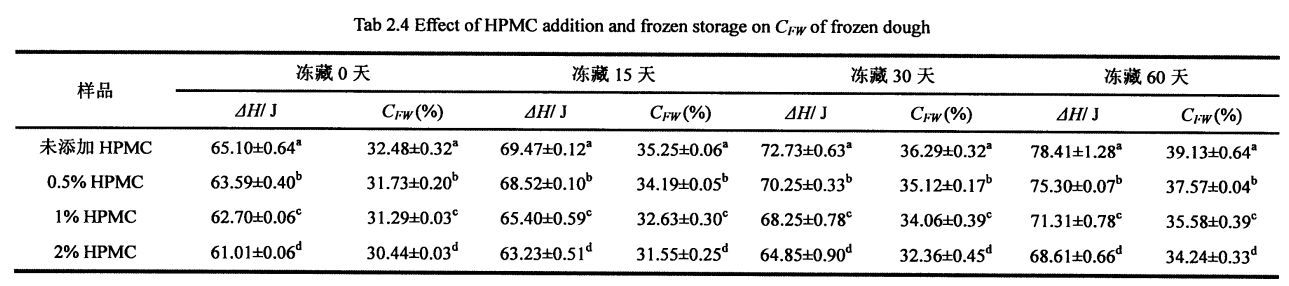

FPMC قوشۇنىشتىن 2.3.5 ۋە توڭلىتىلغان سۇ مەزمۇنى (Gw) نىڭ باشلىنىش ۋاقتى

2.3.6 HPMC قوشۇش ۋە ھاقارەتلەش ۋاقتى

2.4 باب خۇلاسە خۇلاسە

Chapter 3 Effects of HPMC addition on the structure and properties of wheat gluten protein under freezing conditions………………………………………………………………………………………...................24

3.1 تونۇشتۇرۇش ..................................................................................................................................................................................

3.2.1 Experimental materials ............................................................................................................25

3.2.2 Experimental apparatus ...........................................................................................................25

3.2.3 Experimental reagents…………………………………………………………………………. .................. 25

3.2.4 Experimental methods ....................................................................................................... 25

3. Results and Discussion ................................................................................................................ 29

3.3.1 The effect of HPMC addition and freezing time on the rheological properties of wet gluten mass………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….29

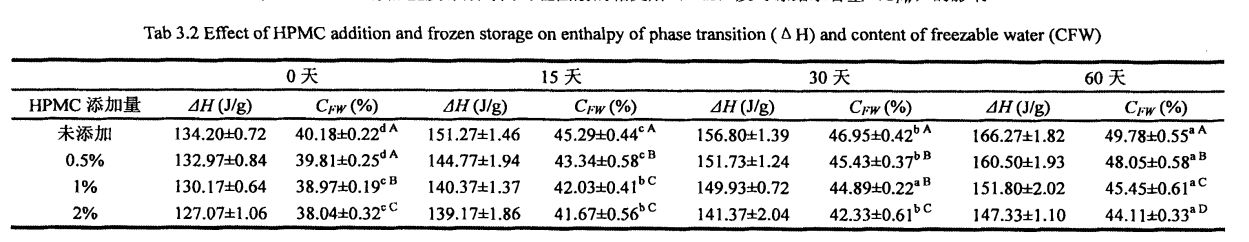

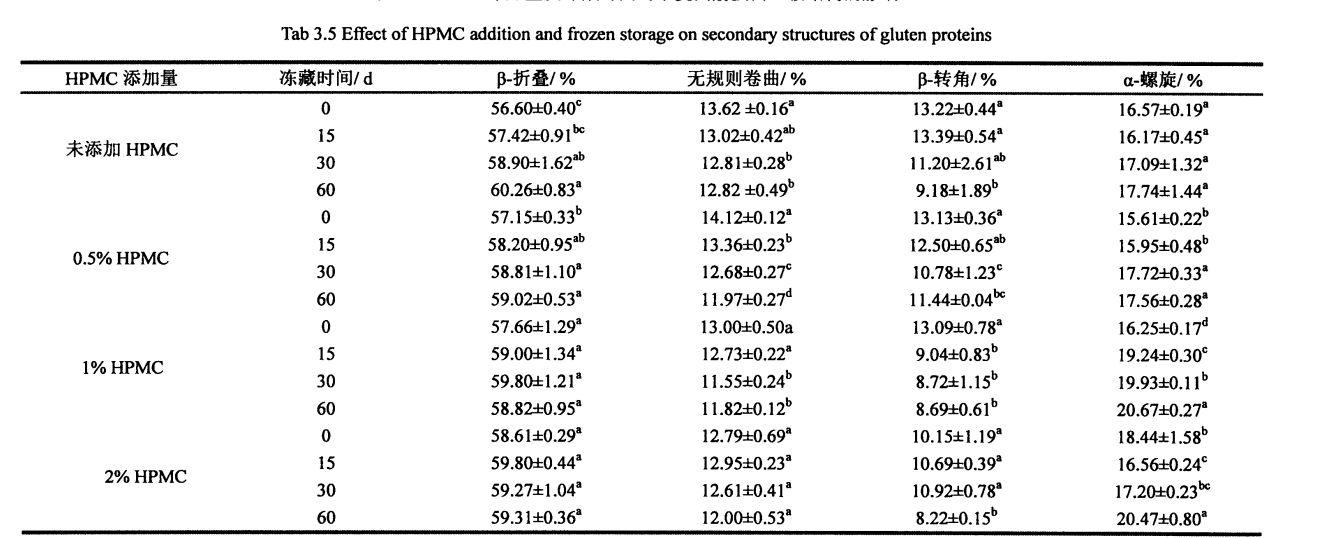

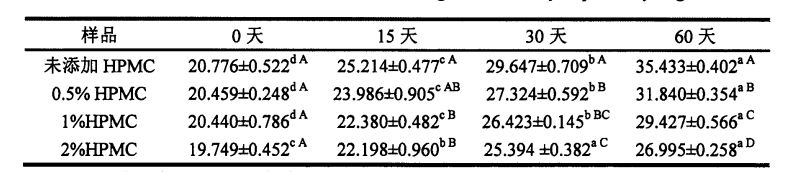

3.3.2 توڭلاتقى بولىدىغان ئاۋاز بېرىش مەزمۇنى (CFW) نىڭ مىقدارى (CFW) نىڭ ساقلاش ۋاقتىنى (كەچكى) قوشقاندا ساقلاش ۋاقتىنىڭ ئۈنۈمى .................................................................wwuwurn.. 30

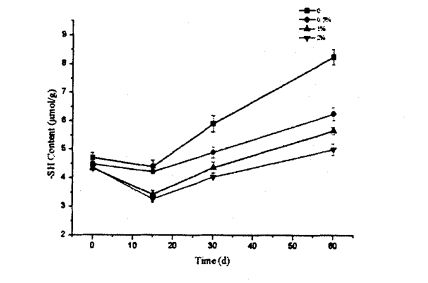

3.3.3 HPMC قوشۇلۇش نىسبىتى ۋە ھەقسىز سۇلفايدرىسنىڭ مەزمۇنى (C Beosel) بار. . 34

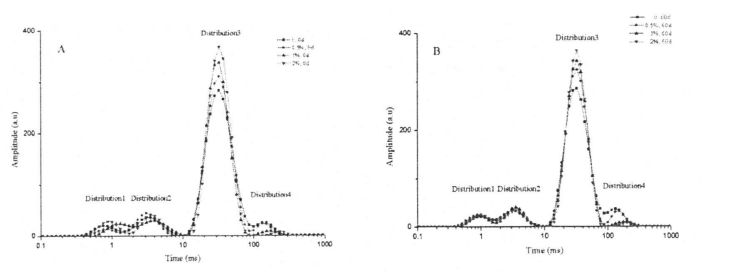

3.3.4 Effects of HPMC addition amount and freezing storage time on the transverse relaxation time (N) of wet gluten mass…………………………………………………………………………………35

HPMC بۇنىڭدىن MPMC بۇنىڭدىن كېيىنكى مىقداردىكى مىقداردا ۋە مۇزلىق ساقلاش ۋاقتى ھەققىدە ساقلاش ۋاقتى

3.3.6 FIPMC قوشۇلۇشى ۋە گللۇېن ئاقسىلىنىڭ يەر يۈزىدىكى گىرۋاپخانىسىنىڭ باھاسى

HPMC نىڭ باھاسى 3.3.7 ئىقتىدار ۋە گىلاسنىڭ مىكرو تور قۇرۇلمىسىنىڭ باھاسى ۋە مۇزاي يېتىش ۋاقتى ۋە مۇزلۇق ساقلاش ۋاقتى ۋە مۇزلۇق ساقلاش ۋاقتى

3.4 باب خۇلاسە خۇلاسە

4-باب HPMC نىڭ ستارخېن ساقلاش شارائىتىدىكى خان جەمەتى ۋە خۇسۇسىيىتىدە

4.1 Introduction .............................................................................................................................. . 44

4.2 Experimental materials and methods ................................................................................. 45

4.2.1 تەجرىبە ماتېرىياللىرى ..................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................

4.2.2 Experimental apparatus ............................................................................................................45

4.2.3 تەجرىبە ئۇسۇلى ....................................................................................................................................................................................................

4.3 Analysis and discussion ........................................................................................................... 48

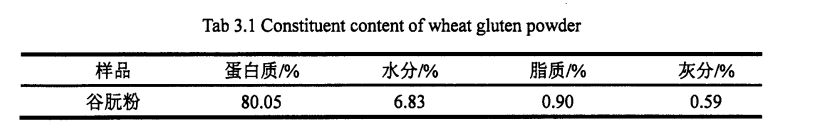

4.3.1 بۇغداي چولپىنىنىڭ ئاساسىي زاپچاسلىرىنىڭ مەزمۇنى ........................................................................... 48

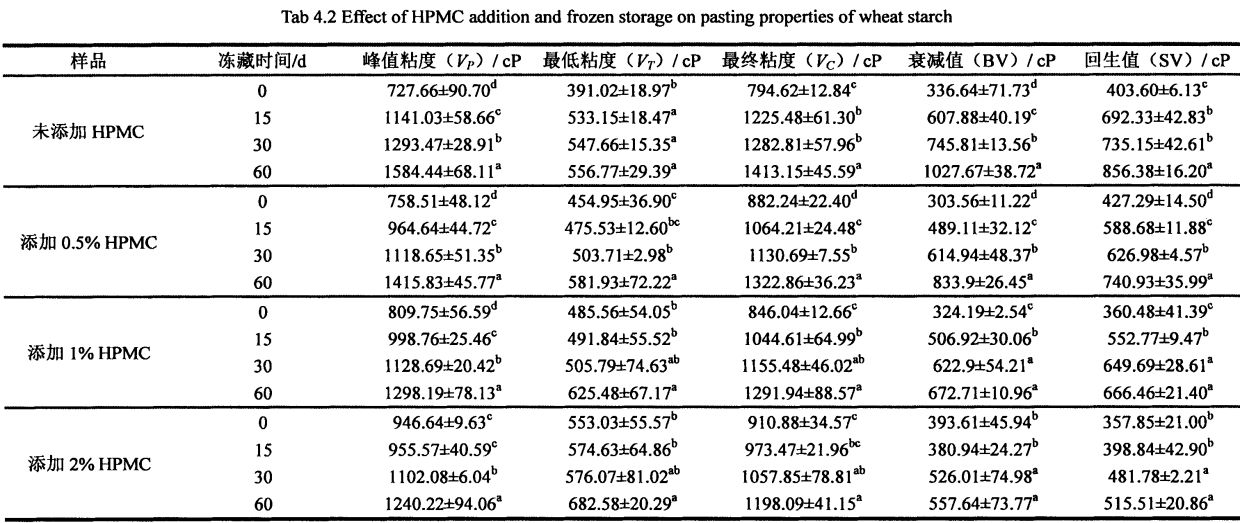

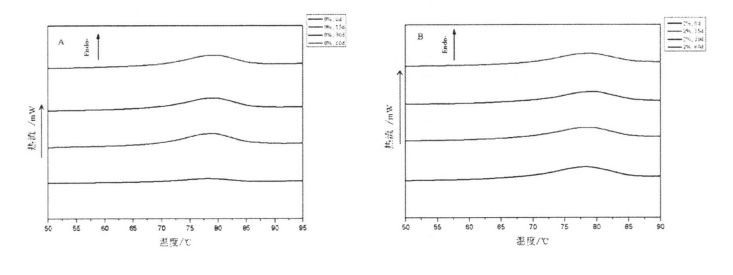

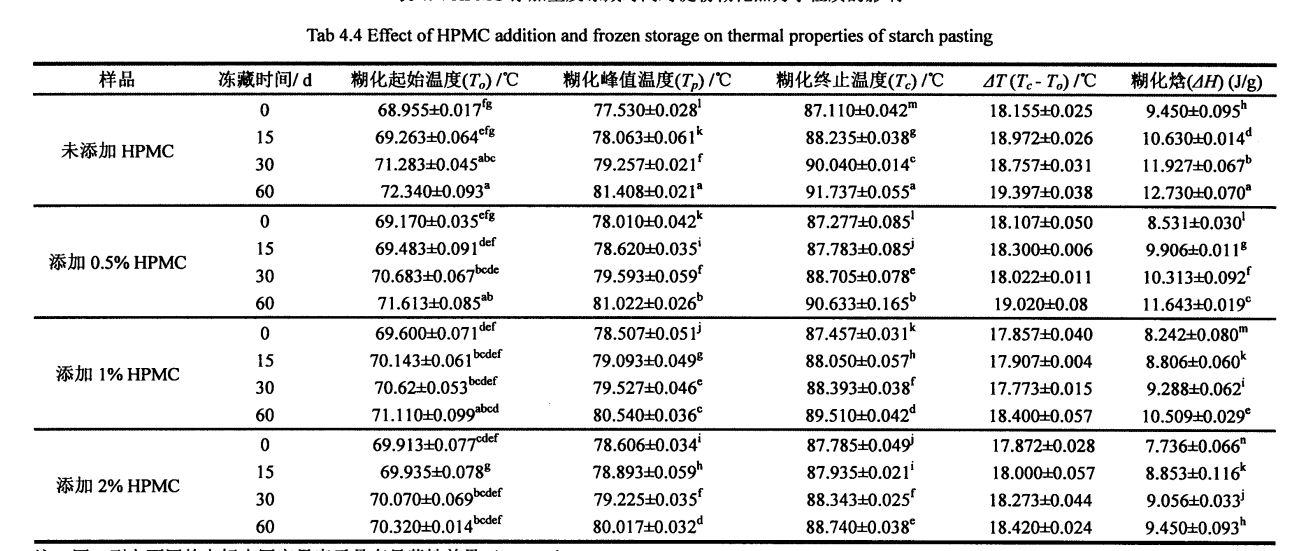

4.3.2 Effects of I-IPMC addition amount and frozen storage time on the gelatinization characteristics of wheat starch……………………………………………………………………………………………….48

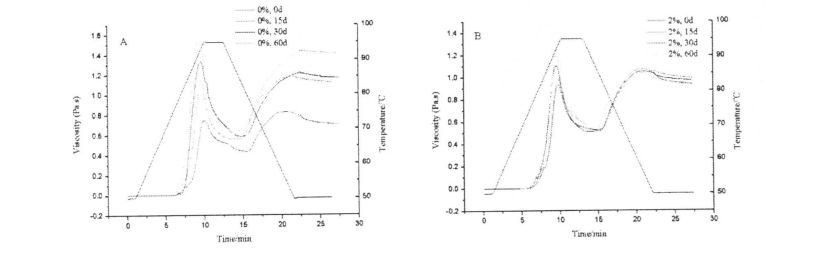

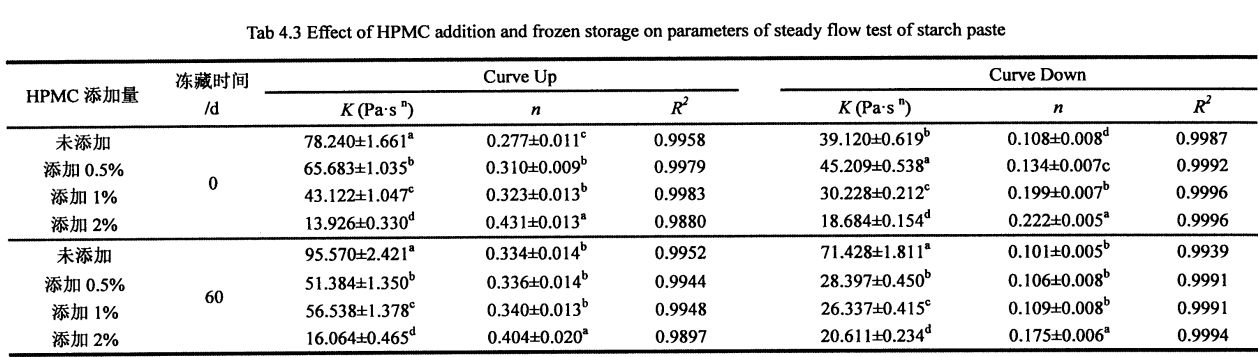

4.3.3 Effects of HPMC addition and freezing storage time on the shear viscosity of starch paste………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………. 52

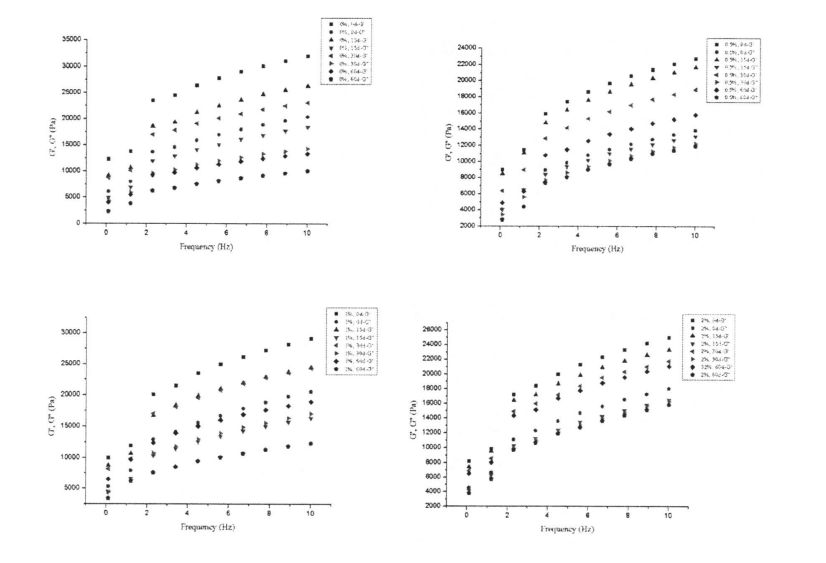

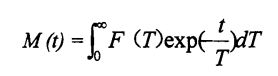

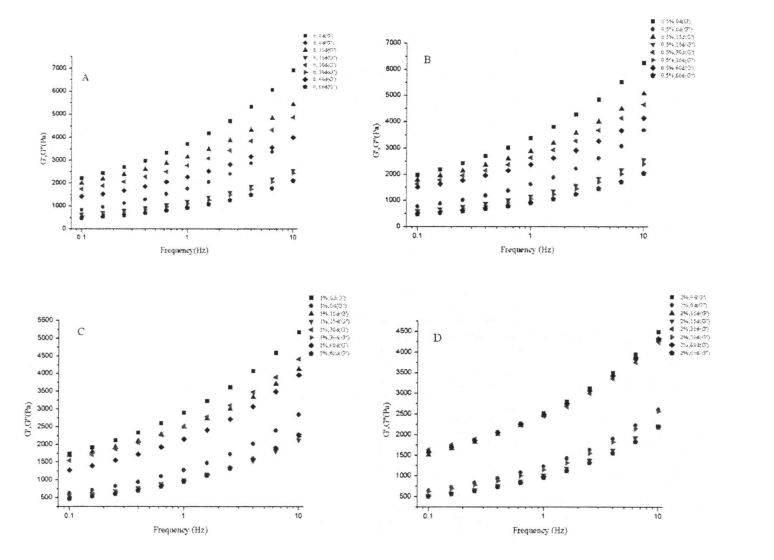

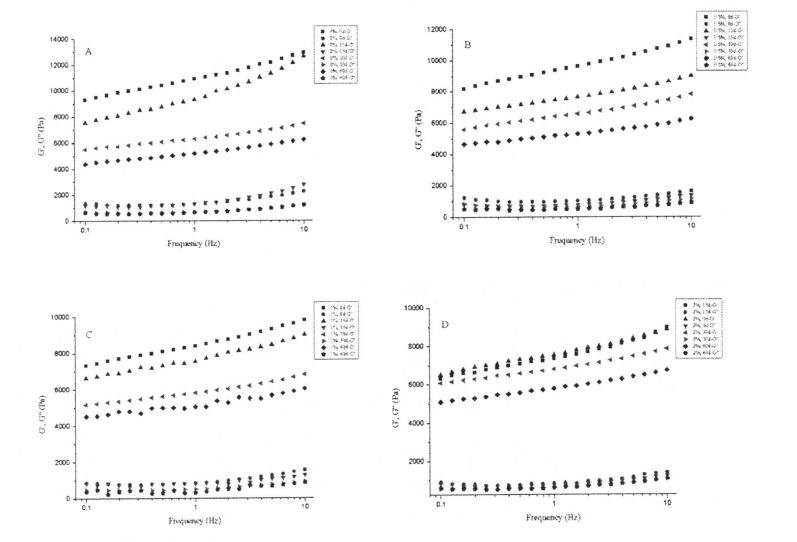

4.3.4 Effects of HPMC addition amount and frozen storage time on dynamic viscoelasticity of starch paste………………………………………………………………………………………………….55

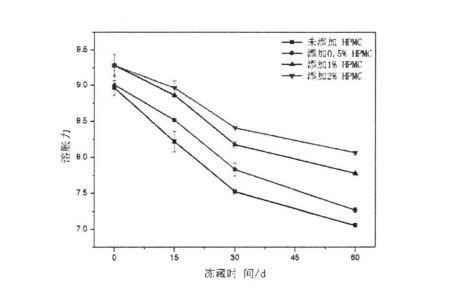

4.3.5 Influence of HPMC addition amount and frozen storage time on starch swelling ability……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….56

4.3.6 I-IPMC قوشۇلۇش مىقدارى . 57

4.3.7 HPMC قوشۇلۇش نىسبىتى ۋە مۇزلۇقنىڭ خەتىرىدىكى ساقلاش ۋاقتى

4.4 باپ خۇلاسە خۇلاسە 6 1

Chapter 5 Effects of HPMC addition on yeast survival rate and fermentation activity under frozen storage conditions………………………………………………………………………………………………. . 62

5.1Introduction .................................................................................................................................... 62

5.2 Materials and methods ............................................................................................................ 62

5.2.1 Experimental materials and instruments ............................................................................. 62

5.2.2 تەجرىبە ئۇسۇلى. . . . . ................................................................................................................... 63

5.3 Results and Discussion ............................................................................................................... 64

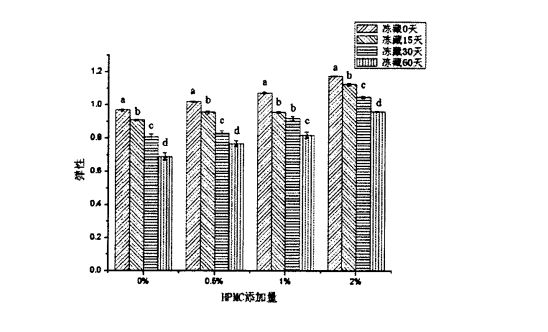

5.3.1 The effect of HPMC addition and freezing time on the proofing height of dough…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 64

5.3.2 Effects of HPMC addition amount and freezing time on yeast survival rate…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………65

5.3.3 ھاقارەتلەش ۋە توڭگۇزنىڭ مەزمۇنى ئۈچۈن HPMC ۋە توڭلىتىش ۋاقتى. »

5.4 باب خۇلاسە خۇلاسە 67

Chapter 6 Conclusions and Prospects ............................................................................................ ………68

6.1 Conclusion ................................................................................................................................. . 68

6.2 Outlook .......................................................................................................................................... 68

مىسال تىزىملىكى

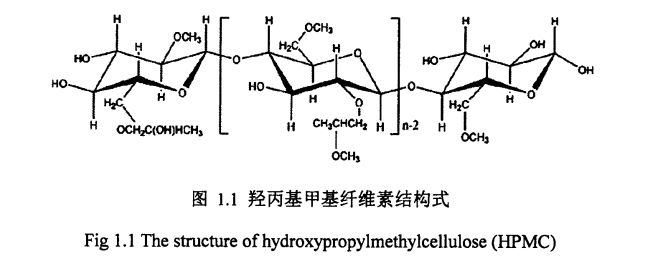

رەسىم 1.1 گىدروسسۋىلدېپىلنىڭ قۇرۇلمىلىق فورمۇللىكىنىڭ قۇرۇلما فورمىسى ................................ . 6

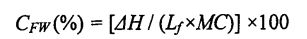

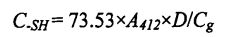

Figure 2.1 The effect of HPMC addition on the rheological properties of frozen dough…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. 15

رەسىم 2.2 نىڭ باھاسى

2.3-رەسىم HPMC قوشۇشنىڭ ئۈنۈمى ۋە ھاقارەتلەش ۋاقتى ۋە توڭلاتقۇ نۇرىنىڭ ئۈنۈمى,

2.4-رەسىم HPMC قوشۇش ۋە تولغان ناننىڭ ئېلخورتىيىتىنىڭ ئۈنۈمى ۋە مۇزدىن ئۆتۈش ۋاقتى . 20

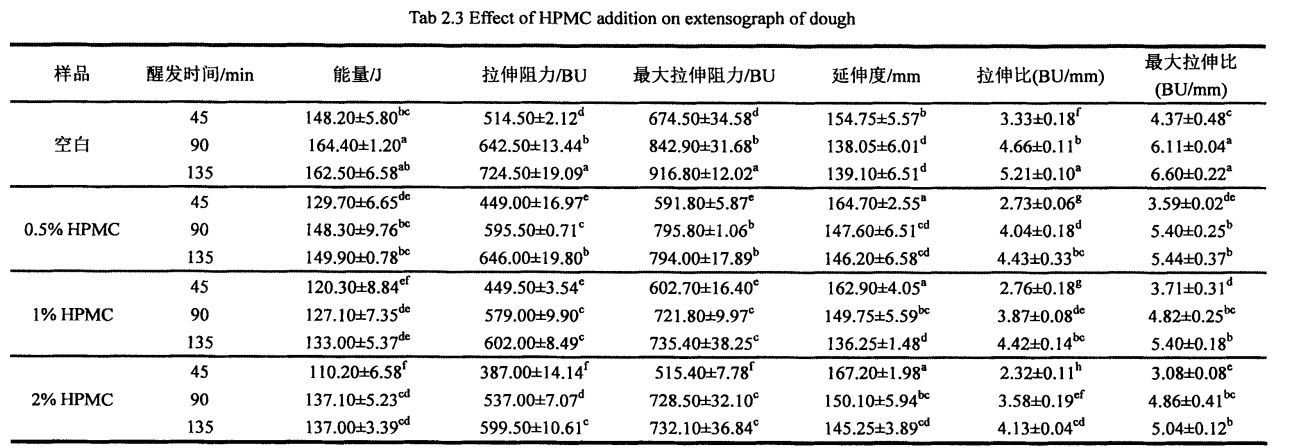

Figure 3.1 The effect of HPMC addition and freezing time on the rheological properties of wet gluten…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………. 30

1-رەسىم 3.2-رەسىمدىكى HPMC قوشۇش ۋە مۇزسىزلىق خۇسۇسىيىدىكى بۇغداينىڭ چېمپىيونلۇقىدىن توڭلىتىش ۋاقتى. . 34

بىر 3.3-رەسىمدىكى HPMC قوشۇش ۋە توڭگۇزنىڭ سۇلفايت نۇرىنىڭ مەزمۇنى بار. 35

رەسىمدىكى HPMC قوشۇلۇش مىقدارى ۋە مۇزسىز ئارام ئېلىش ۋاقتى (n)

EXT 3.5 بۇغداي گولۋىن گوللاندىيەلىك ئاقسىل ۋە ئىككىنچى تۇغۇندىي شەكىللىك

Figure 3.6 Illustration ................................................................................................................ ……….39

Figure 3.7 The effect of HPMC addition and freezing time on the microscopic gluten network structure…………………………………………………………………………………………………………... . 43

4.1-رەسىم 4.1 ستارەتسىز ھايۋاناتلاشتۇرۇش خاراكتېرلىك ئەگرى سىزىق ................................................................................... 51

Starch CareTe نىڭ 42-رەسىملىك قەبرە قەۋىتى. 52

Figure 4.3 Effects of adding amount of MC and freezing time on the viscoelasticity of starch paste……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………... . 57

Figure 4.4 The effect of HPMC addition and freezing storage time on starch swelling ability……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………... 59

چوڭلۇقتىكى HPMC قوشۇش ۋە مۇزلۇق ساقلاش ۋاقتىدىكى ساقلاش ۋاقتى . 59

رەسىم 1.6-رەسىم HPMC قوشۇش ۋە باشلىق ساقلاش ۋاقتى

Figure 5.1 The effect of HPMC addition and freezing time on the proofing height of dough…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………... 66

Figure 5.2 The effect of HPMC addition and freezing time on the yeast survival rate…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………... . 67

يېسىنچى (مىكروسكوپ تەكشۈرۈش) 5.3 مىكرو 10. 68

رەسىم 5.4-رەسىم HPMC قوشۇش ۋە مۇزسىزلىنىش ۋاقتى

جەدۋەل تىزىملىكى

Table 2.1 The basic ingredient content of wheat flour…………………………………………………. 11

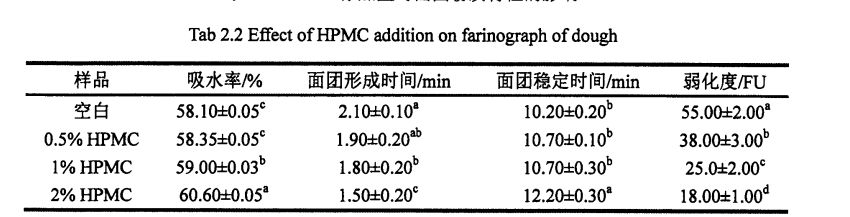

جەدۋەل 2.2 I-IPMC نىڭ ئۈنۈمنىڭ ۋىللىس ئىدراكنىڭ ۋىلايىتىگە قوشۇلۇشنىڭ تەسىرى .................1

جەدۋەل 2. IPMC نىڭ I-IPMC نىڭ IPMC نىڭ راھەت خاسلىقىنىڭ تەسىرى ........................................14

جەدۋەل 2.4 IPPMC ھۆججىتىنىڭ i-ipmc ھۆججەتلىك ۋە توڭلىتىلغان سۇنىڭ (CF خىزمىتى)

جەدۋەل 2.0 ipmc ھۆججىتى ۋە تولغان بولكا خالتىسىدىكى تېز سۈرئەتلىك ۋاقىت ۋە مۇزلاش ۋاقتى ................................................................................................................................................................

جەدۋەل 3.1 گللۇېندىكى ئاساسىي تەركىبلەرنىڭ مەزمۇنى ..................................................................................2

جەدۋەل 3.2 IPMC قوشۇلۇشى I-IPMC قوشۇلۇشى ۋە توڭلاتقۇدا ساقلاش ۋاقتى (Yi IV) ۋە توڭلاتقۇنىڭ ساقلاش ۋاقتى ............................ 31

جەدۋەل 3. HPMC STILE نىڭ ئەڭ يۇقىرى تېمپېراتۇرا (مەھسۇلاتنىڭ تېمپېراتۇرىسى). 33

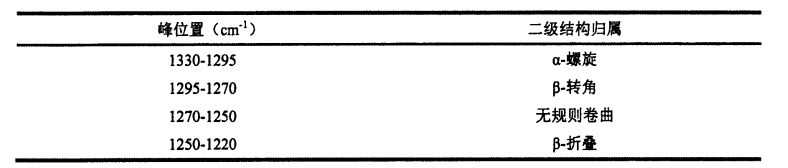

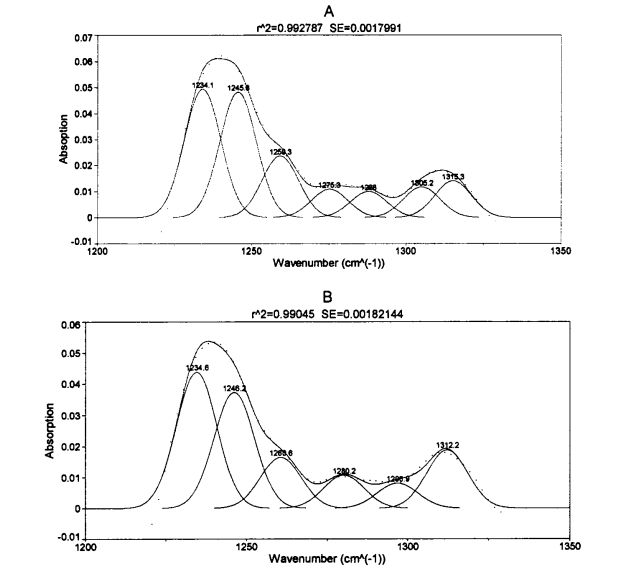

جەدۋەل 3.4 يۇيۇنۇپ بولغان ئىككىلەمچى قۇرۇلمىسى ۋە ئۇلارنىڭ تاپشۇرۇقىنى ۋە ئۇلارنىڭ تاپشۇرۇقلىرى .......... .37

جەدۋەل 3.5 نىڭ 3.5 خىل ئۈنۈمى ۋە بۇغداي يار موتۇnېنتى ئىككى چاقلىق شاھىتىنىڭ ئىككىلەمچى قۇرۇلمىسىدىكى توڭلىتىشنىڭ ئىككىلىنىشى. ................................................................. گىتىم) .40

جەدۋەل 3.6 I-IPMC قوشۇلۇشتىكى I-IPMC قوشۇش ۋاقتى, بۇغداي گلۇتسىكېننىڭ يەر يۈزىدىكى ئاسفوتوبىك ۋاقتى. 41

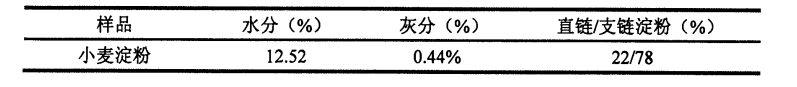

جەدۋەلنى بۇغداي چولپانلارنىڭ ئاساسىي زاپچاسلىرىنىڭ مەزمۇنى ...................................................................

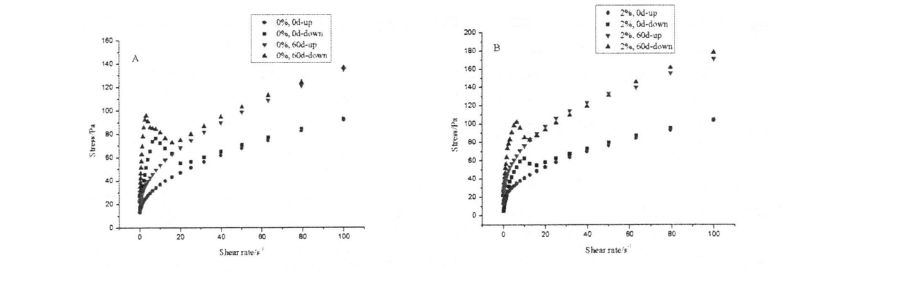

Table 4.2 Effects of HPMC addition amount and frozen storage time on the gelatinization characteristics of wheat starch……………………………………………………………………………………………… 52

Table 4.3 Effects of I-IPMC addition and freezing time on the shear viscosity of wheat starch paste…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………. 55

جەدۋەل 4.4 I-IPMC قوشۇلۇش نىسبىتى

1 - باب مۇقەددىمە

دۆلەت ئىچى ۋە سىرتىدىكى 1.1ReSearse تۇتقۇن ھالىتى

1.1.1-نومۇرلۇق نان

ھورلانغان نان تەكشۈرۈش ۋە ھوردىن چىققاندىن كېيىن خېمىردىن ياسالغان يېمەكلىكلەرنى كۆرسىتىدۇ. جۇڭگونىڭ ئەنئەنىۋى پارتلاش يېمەكلىكى سۈپىتىدە, ھور ناننىڭ ئۇزۇن تارىخى سۈپىتىدە بولۇپ, «شەرق نان» دەپ ئاتالغان. چۈنكى ئۇنىڭ تەييار مەھسۇلاتىدا دېڭىز سۈيى ياكى ئۇزۇنغا سوزۇلغان, تەمى يۇمشاق, تەمى يېمەكلىك, تەمى ۋە ئوزۇقلۇق ماددىلاردا مەرىمانە بار [L] غىدىقلاندۇرىدۇ [l] ئارىمىزدا كەڭ كۆلەمدە ئالقىشقا ئېرىشتى. بولۇپمۇ دۆلىتىمىزنىڭ ئاساسلىق يېمەكلىكى, بولۇپمۇ مىلتى. ئىستېمالچىلار شىمالدىكىدىكى مەھسۇلاتلارنىڭ يېمەك-ئىچمەك قۇرۇلمىسىنىڭ شىمالىي, جۇڭگودىكى ئۇن مەھسۇلاتلارنىڭ% 46 ace ace نىڭ% 48 ى.

1.1.2researchearche توپ مەيدانى

ھازىر, پارنى تاشلاش تەتقىقاتلىرى ئاساسلىقى تۆۋەندىكى تەرەپلەرگە كېلىدۇ:

1) يېڭى ئالاھىدىلىككە ئىگە ھورنى ئېچىش. پار ياراتقان نان خام ئەشيالىرى ۋە ئىقتىدار ئاكتىپ بولۇشتىن, ئىقتىدار ئاكتىپ تۈرلەرنىڭ ئىجازىشىدىن, پارگول-پارگانىيەتنىڭ يېڭىلىنىشى قۇرۇلدى, بۇ ئوزۇقلۇق ۋە ئىقتىدار بار. ئاساسلىق زاپچاس ئانالىزىنىڭ ئوخشىمىغان تەركىبىي قىسمىدىكى خۇسۇسىيەت پارچىسىنىڭ سۈپىتىنى باھالاش ئۆلچىمىنى قۇردى. Fu et a1. () 2015) يېمەك-ئىچمەك تەيبې ۋە پولىفېلوچىلارنى پارچىلاپ, بولاقنى پار ياسىغان بولكا ياساپ, نان تارقىتىلغان ناننىڭ ئوكسىد ناخشىسىنى باھالىدى. Hao & Bata (2012) Barley Blay ۋە زىغىرلىق (بىھۇدە ماددىلاردا مول مول ناننىڭ ئىشلەپچىقىرىلغانلىقى) Shiau et a1. .

2) بىر پىششىقلاپ ئىشلەش ۋە ئالاھىدە ئۇننىڭ ناننى پىششىقلاپ ئىشلەش ۋە بىرلەشتۈرۈشتىكى تەتقىقات. ئۇننىڭ جانلىق ماھىرىنىڭ ياكى يېڭى ئالاھىدە تەنھەرىكەتنىڭ تەسىرى ۋە يېڭى ئالاھىدە تەنھەرىكەتنىڭ تەسىرىگە ۋە يېڭى مەخلىق, يېڭى ئالاھىدە ئىنسا, ئۇن بىر پىششىقلاپ ئىشلەش شەكلىدە ئۇن ئالاھىدە ئىنچىكە ھالقىلارنى ئاساس قىلىپ, ئۇن بىر پىششىقلاپ ئىشلەش مودېلى قۇرۇلدى [7] قۇرۇلدى [7] قۇرۇلدى [7] قۇرۇلدى [7] بېكىتىلدى [7] قۇرۇلدى [7] قۇرۇلدى [7] قۇرۇلدى [7] بېكىتىلدى [7] قۇرۇلدى [7] بېكىتىلدى [7] قۇرۇلدى [7] قۇرۇلدى [7] قۇرۇلدى [7] قۇرۇلدى [7] قۇرۇلدى [7] قۇرۇلدى [7] قۇرۇلدى [7] قۇرۇلدى [7] قۇرۇلدى [7] قۇرۇلدى [7] قۇرۇلدى [7] قۇرۇلدى [7] قۇرۇلدى [7] قۇرۇلدى [7] قۇرۇلدى [7] قۇرۇلدى [7] مەسىلەن, ئوخشىمىغان نۇرغۇن ئايراق بولغان گۈلنى ھەددىدانلىق ئۇسۇلىنىڭ سۈپىتى ۋە ھورنى ھورنىڭ سۈپىتىدىكى تەسىرلەر [7] 81; ھوردا بىر نەچچە موم دانىخورەكنىڭ بىرىكمىسىنىڭ بىرىكمىنىڭ تەسىرى [9j قاتارلىقلار. جۇ, خۇاڭ, & خان (2001) بۇغدات رولنىڭ سۈپىتى خېھ بۇغداي خالتىنىڭ سۈپىتى بىلەن يۈز بەرگەن نان ۋە ھوران نانلىرى بىلەن كۆرۈنەرلىك ئەمەس دەپ قارىدى. جاڭ, EST A1. (2007) يېپاتىلگەن ئاقسىل كاشىلى, ئاقسىل تىت-خەلكەندە ئۇ باغلىنىپ, MLOCITHEAL WINDATRIVE, HMW) ۋە ئومۇمىي ئاقسىل مەزمۇنلىرىنىڭ شىمالىنىڭ ساپور سۈپىتى بىلەن مۇناسىۋەتلىك. كۆرۈنەرلىك تەسىر كۆرسىتىڭلار [11].

3) خېمىر تەييارلاش ۋە ھوردىن ياسالغان نان ياساش تەتقىقات. ئۇنىڭ سۈپىتى ۋە جەرياندا ئېتىبار باھادا پارتلانغانلىق ئىشلەپچىقىرىش جەريانىنىڭ تەسىرىدە تەتقىقات Liu changhong et. (2009) خېمىر كېسەل باسقۇچىدا مۇنداق كۆرسىتىلدى, سۇ قوشۇلغانسى, سۇدىن دەكرى كۆپ قېتىم ئۇتتۇرۇڭ, ئولتۇرۇش ۋاقتى تۇرغۇچى ۋە قىلتاق ئۇنىڭ سەزگۈنى باھالاشتا كۆرۈنەرلىك تەسىر كۆرسىتىدۇ. ئەگەر بۇ جەريان شارائىت ماس كەلمىسە, مەھسۇلاتنىڭ كۆك, قېنىق ياكى سېرىق رەڭنى كەلتۈرۈپ چىقىرىدۇ. تەتقىقات نەتىجىسىدە SouG بېرىلگەن سۇنىڭ مىقدارى% 45 كە يەتتى, ئورۇللاش ۋاقتى 5 مىنۇت, دەل-ئاينىڭ بوغۇلۇش نىسبىتى 6.5,000 ئىدى, ئاق ۋە سەھرانىڭ ئاق بىرىكمىلەر بىلەن تەمىنلەنگەن. خېمىر خېمىرنى كۆنگەندە بىرلا ۋاقىتتا ئۆرۈلۈپ چۈشغاندا, خېمىرنىڭ ئۇ قورۇمىسى, سىلىق, ئېلاستىي ۋە پارقىراق يەر; دومىلىما نىسبەت 3: 1: 1, خېمىر ۋاراق پارقىراق, ھور ناننىڭ ئاق تەنقىدىيلىكى [l to; لى, et A1. (2015-يىلى) Compound Remouded hought ۋە ئۇنىڭ پاردى تەرەپتىكى پروگراممىنىڭ ئىشلەپچىقىرىش جەريانىنىڭ ئىشلەپچىقىرىش جەريانىنى تەكشۈرۈڭ [13].

4) ھوردىن ياسالغان ناننى ياخشىلاشتىكى تەتقىقات. ناشتىلىق ھور سۈپىتىنىڭ قوشۇلۇشى توغرىسىدىكى تەتقىقات ۋە قوللىنىلىدۇ ئاساسلىقى خرۇسغاتلارغا (مەسىلەن, بىر قەدەر خۇلەزم, تەقلىد قىلىش قاتارلىقلارنى ئۆز ئىچىگە ئالغانلار [15] مۇناسىپ بۇ جەريانغا ئوخشاش, تەخمىنەن لايىھىلەش) ۋە باشقا لايىھىلەش ۋە باشقا چىقىم خاراكتېرلىك ئاقسىل ۋە باشقا تۈرلەرنى ئىشلىتىش ئارقىلىق ئوتتۇرىغا قويۇلغان. سېلېك كېسەللىكلىرى (سېلېكك كېسەللىكىدىكى بىمارلارنىڭ يېمەك-ئىچمەك ئېھتىياجى [16.1 CIT.

5) پاراكەندىچىلىك ۋە مۇناسىۋەتلىك نان ۋە مۇناسىۋەتلىك مېخانىزملارغا قارشى تۇرۇش. Pan lijun et al. (2010) بىرىكمە كۆرۈنەكنى تەجرىبە خاراكتېرلىك لايىھىلەش ئارقىلىق ياخشى بولغان ئۈنۈمىگە ئېرىشىش ئارقىلىق [L ئۇنداق ئەمەس. ۋاڭ, كۇنۇپكىلار. () 2015 گولتېر ئاقسىلنىڭ ئامالسىز دەرىجىدىكى نەيمىيلىك ئۇنۋانىغا ئۇچرىغان نەيمىيلىك ئۇنۋانىغا ئۇچرىغان نەيرىلىك ئۇنۋاننىڭ تەسىرىنى تەتقىق قىلغان. نەتىجىدە بۇ سۇ يوقىتىپ قويغان ۋە كلاسسىك يىغىلىش نان ياساشنىڭ ئاساسلىق سەۋەبلىرى بولۇپ, 20].

6) يېڭى فېرمېنتلىق ۋە سورۇنجۇنىڭ ئىلتىماسى. جياڭ, et A1. (2010) Wetomanium sp نى ئىشلىتىش. ھور (گومراخۋانى) پارتارلانغان نانلارنى پارتلاش ئۈچۈن XylLaast (Grustometable بولكىسى بىلەن) ھاسىل قىلدى Gerez, et A1. (2012) ۋېرمېنتلىق ئۇن مەھسۇلاتلىرىدا ئىككى خىل ئۇزۇنلۇق لاپتىكى موتاي باكتېرىنى ئىشلەتتى ۋە سۈپىتىنى يۇقىرى كۆتۈردى [221; Wu, el. (2012) ھەر خىل قىستۇرما كىلاسسىك باكتېرىيە سەھىپىسىنىڭ تەسىرى (لاكتىن كۆچكامىن, لاكتىن پائالىيىتى, لاكتىن پائالىيىتى نانقىسى, ئۇزۇن پاكارۇسېللىق نۇقتا) نىڭ سۈپىتى (كونكرېتلىق ۋە تارىخى, ئىپادىسى) نىڭ سۈپىتى (كونكرېت ھەجىمى) and Gerez, et A1. (2012) لى نەقىش كىسلاتاسى كىسلاتاسىنىڭ ئالاھىدىلىكى ئالاھىدىلىكىنى ئىشلىتىپ, ئۆسۈملۈك مەھسۇلاتلىرىنىڭ تازىلىق ئالاھىدىلىكىنى تېزلىتىپ, پادى ۋە باشقا تەرەپلەرنىڭ توپلاش ئوبنىكىنى تېزلىلەندۈردى.

7) توڭلىتىلغان بولكىنىڭ توڭلىتىلغان داغنىڭ قوللىنىلىشى توغرىسىدىكى تەتقىقات.

بۇنىڭ ئىچىدە پارنى تاش نان ئادەتتە ئادەتتىكى ساقلاش شارائىتىنىڭ تەركىبىدە قېرىندىشىچە, ئۇ بولۇشى كېرەك, بۇ بىر مۇھىم ئايفون ئىشلەپچىقىرىش ۋە بىر تەرەپ قىلىشنى چەكلەش مۇھىم ئامىل. ئابىدە, ھورلانغان بولكىنىڭ سۈپىتى تۆۋەنتۈرۈلگەندىن كېيىن - توسىقى قۇرغۇرۇش, قەبرىستانلىقنىڭ سۈپىتىگە, قەبرىستانلىق ۋە ساز-شارى ۋە سابىق بولۇش نىسبىمۇ ئۆرلەش, ھەزىم قىلىش ۋە سۈمۈرۈلۈش ۋە سۈمۈرۈلۈش نىسبىتى تۆۋەنلەيدۇ, ئوزۇقلۇق قىممىتى تۆۋەنلەيدۇ, ئوزۇقلۇق قىممىتى تۆۋەنلەيدۇ, ئوزۇقلۇق قىممىتى تۆۋەنلەيدۇ, ئوزۇقلۇق قىممىتى تۆۋەنلەيدۇ, ئوزۇقلۇق قىممىتى تۆۋەنلەيدۇ, ئوزۇقلۇق قىممىتى تۆۋەنلەيدۇ, ئوزۇقلۇق قىممىتى تۆۋەنلەيدۇ, ئوزۇقلۇق قىممىتى تۆۋەنلەيدۇ. بۇ ئۇنىڭ Charf ھاياتىغا تەسىر كۆرسىتىدۇ, ئەمما يەنە نۇرغۇن ئىسراپچىلىق پەيدا قىلىدۇ. ئىستاتىستىكىغا قارىغاندا, قېرىش سەۋەبىدىن يىللىق زىيان تېخىمۇ كۆپ زىياننىڭ سانىنىڭ% 3 ى بار. 7%. كىشىلەرنىڭ تۇرمۇش سەۋىيىسىنىڭ ئۆسۈشى ۋە يېمەكلىك سانائىتىنىڭ تېز تەرەققىي قىلىشى ۋە ئۆسۈۋاتقان مۇھىم تەرەققىيات مەھسۇلاتلىرىغا, ئۇزۇن ساقلاش ھاياتتىن يۇقىرى سانائەت, ئۇزۇن ساقلاش ھاياتقا قانداق يەتكۈزگەندە, شۇندىلا شۇنچە ئۇزۇن ھالەتتىكى تېخنىكا مەسىلىسى ۋە ئاسان داۋاملىق تېجەشلىك. بۇ ئارقا كۆرۈنگۈدەك, توڭلىتىلغان خېمىرۇلۇمغا ئاساسلاندى, شۇنداقلا تەرەققىياتى يەنىلا شۇنداق كۆتۈرۈلۈپ كەلدى.

1.1.3.330 توڭلىتىلغان خېمىر

توڭلىتىلغان خېۋى تەرىپىدىن 1950-يىللاردا تەرەققىي قىلغان ئۇن مەھسۇلاتلىرى ئىشلەپچىقىرىش ۋە ئىشلەپچىقىرىشنىڭ يېڭى تېخنىكىسى. ئۇ ئاساسلىقى بۇغداي ئۇننىڭ ئاساسلىق AW ماتېرىيالى ۋە سۇ ياكى شېكەر سۈپىتىدە ئاساسلىق ياردەمچى ماتېرىيال سۈپىتىدە ئىشلىتىشنى كۆرسىتىدۇ. قاپلانغان, قاچىلانغان ياكى ئورالغان, باشقا تەرەپلەر مەھسۇلاتنى مۇزلاپ كەتكەن ياكى توڭلىتىش ئۈچۈن, كېرەكلىك مەھسۇلاتلارغا نىسبەتەن كېرەكلىك, دەلىل-ئۇچرىغان مەھسۇلاتلارنى 251] يېتىدىكەن.

ئىشلەپچىقىرىش مۇساپىسىگە ئاساسەن, توڭلىتىلغان خېيىقەسكە ئاساسەن تۆت خىل ھالەتكە بۆلۈنۈشكە بولىدۇ.

جاۋاب) توڭلىتىلغان خېمىر ئۇسۇلى: خېمىر بىر پارچە پارچىلىنىپ, توڭلىتىلغان, توڭلىتىلغان, ئەۋەتىلگەن, ئىسپاتلانغان ۋە پىشۇرۇلغان ۋە پىشۇرۇلغان (پىشۇرۇش قاتارلىقلار)

B) جۇنتىغا بۇرۇنقى ۋە يېقىشلىق ئۇسۇلىنى بىر تەرەپتە: خېمى ئېلان قىلىنغان, بىرى تېز توڭلىتىلغان, بىرى توڭلىتىلغان, بىرى ئىسپاتلانغان, بىرى ئىسپاتلانغان, بىرى پىشۇرۇلغان (پىشۇرۇش قاتارلىقلار)

c) ئالدىن پىشۇرۇلغان خېمىر خېمىر: خېزى بىر پارتلاش قىلىپ قاتلانغان, خېلى (مەلۇم دەرىجىدە پىشۇرۇلغان.

D) تولۇق بىر تەرەپ قىلىنغان خېمىر: خېزى بىر پارتلاش ۋە شەكىللەنگەن بولۇپ, بولۇپمۇ تەكشۈرۈپ, تولۇق دەلىللىدى, ئاندىن تولۇقمۇ پىشۇرۇلغان, ئەمما توڭلىتىلغان, توڭلىتىلغان, توڭلىتىلغان, توڭلىتىلغان, توڭلىتىلغان, توڭلىتىلغان, توڭلىتىلغان, توڭلىتىلغان, توڭلىتىلغان, توڭلىتىلغان, توڭلىتىلغان, توڭلىتىلغان.

توڭلىتىلغان خېمىرنىڭ بارلىققا كېلىشى, قېلىپلاش سېيىش, قېلىپلاشقان پانانى مەھسۇلاتلىرىنى ئۈنۈملۈك تۆۋەنلىتىدۇ, ئىشلەپچىقىرىش ئۈنۈمىنى ئۈنۈملۈك ھەل قىلالايدۇ, ئىشلەپچىقىرىش ئۈنۈمىنى ئاشۇرۇش ۋە ئەمگەك كۈچىنى ئۆستۈرەلەيدۇ. شۇڭلاشقا, ستار يېمەكلىكلەرنىڭ ياشانغان ھادىسىسىنى ئۈنۈملۈك چەكلەيدۇ, مەھسۇلاتنىڭ قويۇق تۇرمۇشىنى كېڭەيتىشنىڭ تەسىرى. شۇڭلاشقا, بولۇپمۇ ياۋروپا, ئامېرىكا ۋە باشقا دۆلەتلەر ۋە چاققانلىق تاتلىق نان (توڭلۈكى), بولكا ئۆرۈلۈپ, نان (قولۇڭ), فىرانسۇزچە سومكا, FORK), POLD), POLD), POLD), POLD), ساقلانما

تورتلار ۋە باشقا پالۋان مەھسۇلاتلىرىنىڭ ئوخشىمىغان ئۇنۋانلىرى بار [26-27]. تولۇق بولمىغان ستاتىستىكا بويىچە, 1990-يىلغا بارغاندا, ئامېرىكىدىكى كېمەنىڭ% 80 ى توڭلىتىلغان خېخىدىن ئىشلىتىلگەن. ياپونىيىدىكى% 50 كاۋىپى يەنە توڭلىتىلغان خېمىرنى ئىشلەتكەن. 20-ئەسىر

ئالدىنقى ئەسىرنىڭ 90-يىللىرىدا, توڭلىتىلغان خېمىر پىششىقلاپ ئىشلەش تېخنىكىسى ئوتتۇرىغا قويۇلدى. پەن-تېخنىكانىڭ ئۈزلۈكسىز تەرەققىي قىلىشى ۋە كىشىلەرنىڭ تۇرمۇش سەۋىيىسىنى ئۈزلۈكسىز مۇكەممەللەشتۈرۈپ, فىلاڭ مەيدانىنىڭ جاھىللىق دەرىجىسىنىڭ كەڭ تەرەققىيات ئىستىقبول ۋە غايەت زور تەرەققىيات بوشلۇقى بار كەڭ كۆلەمدە تەرەققىيات مەيدانلىرى بار

توڭلىتىلغان خېمىرنىڭ 1.1.4-پاراكەندىسى ۋە خىرىس

توڭلىتىلغان خېمىر تېخنىكىسى شۈبھىسىزكى ئەنئەنىۋى كىشىلەرنىڭ ئەنئەنىۋى جۇڭگونىڭ سانائەتلەشتۈرۈش ئىشلەپچىقىرىش ناھايىتى مۇمكىن. قانداقلا بولمىسۇن, بۇ بىر تەرەپ قىلىش تېخنىكىسى يەنىلا بەزى قىستۇرمىلاردا يەنە بەزى قىستۇرمىلار بار, بولۇپمۇ بارلىق بوشلۇق, كونكرېت ئىمارەت, مۇۋاپىق ئاۋاز, سۇ يوقىتىش, ناچار تەمى, تەمىنى قوبۇل قىلىش, تەمكىنلىك, تەمىنى قوبۇل قىلىش, تەمكىنلىك ۋە سۈپەتسىزلىكىنى دەلىللەيدۇ. ئۇنىڭدىن باشقا, توڭلىتىش سەۋەبىدىن

خېزى توپ (نۇرى, ئاقسىل, كەرشا, مىكرو, سۇلۇق بەلگە تارتىش كۈچى), كۆپ خىل ئارخىپ كۆرۈنمە يۈزى), كۆپ خىل ئارخىپ كۆرۈنكىلى) يۇمشاق دېتال سىستېمىسى 1281.

كۆپىنچە تەتقىقاتلاردا بايقىلىشىچە, مۇزرايىنىڭ شەكىللەندۈرۈش ۋە مۇزلۇق يېمەكلىكلەرنىڭ شەكىللىنىش ۋە ئېشىشىنى كەچۈرۈم قىلغانلىقى بايقالغان مەھسۇلات سۈپىتىنىڭ ناچارلىشىشىغا ئىنتايىن مۇھىم ئامىللار [291]. مۇز خرۇستاللىرى پەقەت يېگانە ساندۇقنىڭ ھايات قېلىش نىسبىتىنى تۆۋەنلىتىدۇ, ئەمما Starge StargellinitYmetinitymallinitYment ۋە Gelit Slocells غا تەسىر كۆرسىتىپ, يېتىلىش ھۈجەيرىلىرىگە تەسىر كۆرسىتىدۇ, يېتىلىش ھۈجەيرىلىرىگە تەسىر كۆرسىتىدۇ, بۇ كلايتۇرا ئەخلەتلەرنى ئازايتىش ۋە تارقىتىش. ئۇنىڭدىن باشقا, توڭلىتىلغان ھالەتتە, بازارنىڭ داۋالغۇش مۇز كىرىستاللىرىنىڭ ترۇستاللىشى سەۋەبىدىن مۇز كىرىستالنى كەلتۈرۈپ چىقىرىدۇ [30]. شۇڭلاشقا, خلانېتىسى ۋە Starch نىڭ پايدىسىز تەسىرى قانداق قىلىپ يۇقارقى مەسىلىلەرنى ھەل قىلىشنىڭ مۇھىملاس كېلىدىغان مەسىلە, ئۇ يەنە قىزىق تەتقىقات مەيدانى ۋە يۆنىلىشىمۇ بار. ئۆتكەن ئون يىلدا, نۇرغۇنلىغان تەتقىقاتچىلار بۇ ئەسەر بىلەن شۇغۇللىنىپ, بىر ئاز مول تەتقىقات نەتىجىسىنى قولغا كەلتۈردى. قانداقلا بولمىسۇن, بۇ ساھەدە يەنىلا ئۈزۈلۈپ قارىمىغان, بىر قىسىم ئومۇملاشقان ۋە تالاش-تارتىش بار مەسىلىلەر: بۇنىڭغا ئوخشاش, مەسىلەن:

بىر) توڭلىتىلغان جانلىقنىڭ سۈپەتنىڭ سۈپەتلىكىنى قانداق چەكلەشنى قانداق چەكلەش, بولۇپمۇ بىر مەسىلە خېمىر, يېكچ, يېزاغ ۋە ئېچىلىشتىكى ئۈچ چوڭ زاپچاسنىڭ قۇرۇلۇشى ۋە خۇراقلىشىشى كېرەك. بۇ تەتقىقات ساھەسىدىكى قىزىق نۇقتىلار ۋە نېگىزلىك مەسىلىلەر

B) چۈنكى ئوخشىمىغان تىپتىكى ئۇن مەھسۇلاتلىرى ۋە ئوخشىمىغان مەھسۇلات مەھسۇلاتلىرىدىكى پەرقلەر بىلەن پەرقلىق ئەھمىيەتكە ئىگە بولغان, يەنىلا ئالاھىدە مەھسۇلات تىپلىرىنى بىرلەشتۈرۈشتە ئالاھىدە تەتقىقاتنىڭ تەرەققىياتىغا مۇقەپشە مۇنداق دېدى:

C) يېڭى توڭلىتىنى كېڭەيتىش, يەنى يېڭى توڭلىتىلغان خېمىر سۈپىتىنى ئاشۇرىدۇ, بۇ ئىشلەپچىقىرىش كارخانىلىرىنى ئەلالاشتۇرۇش ۋە مەھسۇلات تىپىنىڭ يېڭىلىنىشى ۋە ئىشلەپچىقىرىشتا يېڭىلىنىشى بىلەن پايدىلىق. ھازىردا يەنىلا تېخىمۇ كۈچلۈك بولۇشى ۋە كېڭەيتىش كېرەك.

D) گىدرولوگېننىڭ توڭلىتىلغان خېمىر مەھسۇلاتلىرىنىڭ سۈپىتىنىڭ سۈپىتى ۋە مۇناسىۋەتلىك مېخانىزملىرى يەنىلا داۋاملىق تەتقىق قىلىشقا ۋە سىستېمىلىق چۈشەنچە كېرەك.

توڭلىتىلغان خېمىرنىڭ 1.1.5researse بالدىس ئورنى

توڭلىتىلغان خېمىرنى كۆزدە تۇتۇپ, توڭلىتىلغان بىر يۆتەل تېخنىكىسىنىڭ يۇقارقى مەسىلىلەرنى ساقلاش ۋە ياخشىلىنىشى, توڭلىتىلغان خېمىردىكى مەھسۇلاتلارنى ياخشىلاش تەتقىقاتى ۋە باشلانغان ھەرىكەتلەر رايونىنىڭ قۇرۇلمىسى ۋە خالايىسىدىكى ئۆزگىرىش مېخانىزىمىدىكى ئۆزگىرىشلەرنى كۈچەيتىدۇ ۋە باشتېما خاراكتېرلىك تەتقىقاتتىكى بىر مەسىلە. كونكېرت جەھەتتىن ئېيتقاندا, يېقىنقى يىللاردىكى ئاساسلىق دۆلەت ئىچى ۋە سىرتىدىكى ئامېرىكا تۆۋەندىكى نۇقتىلارغا ئەھمىيەت بېرىدۇ:

I. پارتلاشنىڭ قۇرۇلۇشى ئەندىشىسىنىڭ ئۆزگىرىشىدە, بىئولوگىيىلىك ماكرومولوكويىسىنىڭ قۇرۇلمىسى بار, توڭلىتىلغان ساقلاش ۋاقتىنى (ئاقسىل, كراخكا قاتارلىقلارنىڭ ئۆزگىرىشى) مەسىلەن, مۇز كىرىستال دېگۈدەك كېڭەيتىلىدۇ. ئوتتۇراھال ۋە ئېشىش ۋە ئۇنىڭ سۇ دۆلەت ۋە تارقىتىش مۇناسىۋىتى; بۇغداي گل ئېتېن ئاقسىل قۇرۇلمى قۇرۇلمىسىنىڭ ئۆزگىرىشى ۋە مال-مۈلۈكلىرى ئۆزگىرىدۇ [31] STARCH قۇرۇلمىسى ۋە مۈلۈكنىڭ ئۆزگىرىشى مەتبەئە مىكرو تازىلىق ۋە مۇناسىۋەتلىك خۇسۇسىيەتتە ئۆزگىرىش 361.

تەتقىقاتتا كۆرسىتىلىشىچە, توڭلىتىلغان بىر تەرەپ قىلىش خۇسۇسىيىتى: 1 بولسا (1) توڭلىتىش جەريانىنى پەسەيتىشنىڭ ئاساسلىق سەۋەبىلىرى: يېقىشلىق ياشاشنى, ئۇنىڭ ئېچىلىش مۇراسىتى ۋە ئۇنىڭ كۈتۈنۈش پائالىيىتى كۆرۈنەرلىك تۆۋەنلىدى. 2) خېمىرنىڭ ئۈزلۈكسىز ۋە تولۇق تور قۇرۇلمىسى ۋەيران بولۇپ, خېمىرنىڭ ھاۋا تۇتۇلۇشىنىڭ ئالدىنى ئالىدۇ. قۇرۇلما كۈچى زور دەرىجىدە تۆۋەنلىتىلىدۇ.

II. توڭلىتىلغان خېمۇل سۇيۇق ئىشلەپچىقىرىش جەريانىنى ئەلالاشتۇرۇش, توڭلىتىش شارائىتى ۋە فورمۇلا. توڭلىتىلغان خېمۇ توڭ, تېمپېراتۇرا كونترول قىلىش, قوغداش شەرتى, توڭلىتىش نىسبىتى, Muluten ئاقسىلنىڭ مەزمۇسى ۋە ئېرىتىش ئۇسۇللىرىنىڭ ھەممىسى توڭلىتىلغان خېمىرغا تەسىر كۆرسىتىدۇ [7]. ئومۇمەن قىلىپ, چوڭلۇقى تېخىمۇ كۆپ تارقىلىپ, تېخىمۇ كۆپ مۇز ئۈزۈلمە ئەرزان باھالىق سوممى ھاسىل قىلىدۇ, تۆۋەن توڭلىتىش نىسبىمۇ توڭلىتىش نىسبىمۇ ئۇزۇن مۇددەتلىك تارقىتىلمايدىغان چوڭ مۇز كىرىستال ئىشلەپچىقىرىدۇ. ئۇنىڭدىن باشقا, ئۈزلۈكسىز پەسىل خاراكتېرلىك تېمپېراتۇرىدا تۆۋەن دەرىجىدىكى تېمپېراتۇرا (CTA) (CTA) نى ئىشلەپچىقىرىپ, تەننەرخى يۇقىرى, ئەمما چىقىمى, ئەمەلىي ئىشلەپچىقىرىش ۋە سوغۇق زەنجىرسىمان تىرانسپورتى ئادەتتە كىچىك. بۇنىڭدىن باشقا, توڭلىتىش تېمپتىنىڭ ئەۋرىشىملىكىنىڭ داۋالىنىشى تۈنتالشېل دېزىنقا كەلتۈرۈپ چىقىرىدۇ, بۇ خېمىنىڭ سۈپىتىگە تەسىر كۆرسىتىدۇ.

III. خۇرۇچ ئىشلىتىش ئۈچۈن خۇرۇچ ئىشلىتىش ئۈچۈن توڭلىتىلغان خېمىرنىڭ سۈپىتىنى يۇقىرى كۆتۈرۈش. مەسىلەن, توڭلىتىلغان ھەرىكەتنىڭ ئوخشىمىغان نۇقتىسىنىڭ سۈپىتىنى يۇقىرى كۆتۈرۈش ئۈچۈن, نۇرغۇن تەتقىقاتچىلار ئاساسلىقى تۆۋەندىكى نىسبەت, I) پىشجامىدىن پىششىقلاپ ئىشلەش, مەسىلەن, دېگەندەك Amylase; II) Monoglycerite Steage, چېسلا, SSL, CSL, چېسلا قاتارلىق پىچاق. III) Antixididans, Ascorbic كىسلاتاسى قاتارلىقلار. % IV) Polysacchralide سۇdroclows, مەسىلەن گۇيار سېغىز, مەسىلەن گابىر سېمبۇم, كونجاكېرلىق, رونيۇجاكې بازىرىغا ئوخشاش, ناتيزاك بورىنى قاتارلىقلارغا ئوخشاش. V) شۈ, & A1 قاتارلىق ئىقتىدار ماددىلىرى. (2009) مۇز-يۇلتۇزلارنى توپادىن قويۇۋەتكەن ئاقسىلنى قوشتى ۋە ھۆل گلۇتېن ماسقىنى قوشۇپ, خلان بەش ئاقسىل ۋە ئىقتىدارنىڭ قۇرۇلمىسى ۋە ئىقتىدارىنى تەتقىق قىلدى ۋە تەتقىق قىلىنىدىغانلىقىنى ئېيتتى.

Ⅳ. AntiFree نى ھەشەمەتلىك ۋە يېڭى سېلىك يۇڭ ھەۋەسكارلىرىنى بېقىش [58-59]. SaSano, et A1. (2013-يىلى) ئارىلاشما دېڭىز قىرغىقىلىق يېقىملىق يېقىملىق يېقىملىق مۇسابىقىسى ۋە S12I, Yu, Yu.

1.1.6 توڭلىتىلغان خېمىر سۈپەتنى ياخشىلاشتا

سۇdrocolhone نىڭ خىمىيىلىك خاراكتېرى (گلۇكوزا, رەجۇق, خىمىيىلىك, خىيانەت, ئىنسانلار, مانوۋوس قاتارلىقلار) دىن تەركىب تاپقان كۆپ قۇتۇپلۇق خاراكتېرى 0 [ 1-4. Glycosidic Bond ياكى / and a. 1 - "6. Glycosidic Bond ياكى B. 1-4. تېرىش ئۆسۈملۈك بورۋاكېر بورى, گۈن گوم, گۈن گوم كوماندىسى, مەسىلەن شىتاخاندا سېغىز. يېمەكلىك سىستېمىسىدىكى سۇ ئىشلىتىش, دۆلەت ۋە تارقىتىش يېمەكلىكلىرى كۆپ ئىقتىدارلىق, سۇ - ئوكېركسوردۋانلىقنىڭ كەڭلىكى ۋە سۇ - ئوكۇل چېچىلىپ كېتىش ۋە سۇ چىقىرىش ئىقتىدارى ئىنتايىن ماس كېلىدۇ. شۇنىڭ بىلەن بىر ۋاقىتتا ئېگىزلىك, مۇقىملاشتۇرۇش ۋە سۇنىڭ ئۆزلىرى بىلەن زىچ مۇناسىۋەتلىك ئۇن مەھسۇلاتلىرىنىڭ يېمەكلىك پىششىقلاپ ئىشلەشنى ئۆز ئىچىگە ئالىدۇ. ۋاڭ شىنت al. (2007) ئورتاق پوستىدىكى پولىسالرىرورتۇرى ۋە ياتاقلىرىنىڭ ئەينەك ئۆتۈش تېمپېراتۇرىسىنى تەتقىق قىلىش نەتىجىسى [631. ۋاڭ يىشۇڭ قاتارلىقلار. (2013) ھەر خىل گىدروفىل تىلى كولولىدىن تەركىب تاپقان خېمىرنىڭ ئېقىشىنى كۆرۈنەرلىك ئۆزگەرتەلەيدۇ. خۇسۇسىيەتنى ئۆزگەرتىپ, خېمىلنىڭ تەرەققىياتىنى ياخشىلاپ, خېمىرنىڭ ئېفىقلىنىشىنىڭ ۋەيۋىسىنىڭ ئېساچانلىقنى ئاشۇرۇش, ئەمما خېمىرنىڭ دۇنيانى قىسقارتىڭ [ئۆچۈرۈش.

1.1.7 FIANDROXINGPREPPYL MEETLEL STOULOSE (HydroxyPripyl methyl mythyl metuulos, i-ipmc)

Hydroypropyl Methyl Metululse (Hydroyyp Bellulpyl MydroyLspyl ۋە Mypmc) شېئىرىلنىڭ ھۈجەيرىسىنى قىسمەن پەيدا قىلىدۇ. ئامېرىكا بانكىسى

تىمىچى مولېكۇلا زايومى ۋە كىرىستال زايومىدىكى ھىمروگېن زايومى سەۋەبىدىن, Calululose نىڭ ئىلتىماسىنىڭ كەمچىللىقىنى چەكلەيدۇ. قانداقلا بولمىسۇن, HPMC نىڭ يان سوسى پەسلىدىكى ئورۇنلاشتۇرۇشنىڭ بولۇشى يوپۇرماقلىق ھارامچا زايوكىنىڭ ئارىسىدا, ئۇنى تېخىمۇ گىدروفىل كىچىك قىلدى. سېلائىلنى قۇلايدىكى بارلىق گىدروفىللىق بولۇپمۇ ئۇنىڭ ئۆزگىچە ئەسلىگە كەلتۈرگىلى بولىدىغان تېنچېمو-مايلىق خاسسىقى سەۋەبىدىن, HPMC ھەمىشە كونترول قىلىنىپ كەتكەن زەھەرلىك چېكىملىكنىڭ كاپسۇل زاپچاسلىرى سۈپىتىدە ئىشلىتىلىدۇ. يېمەكلىكلەردە, HPMC يەنە ساۋاقەت, ئېغىلارغۇچىلار, ئېلاۋۇلكۇس قاتارلىقلارمۇ ئىشلىتىلىدۇ ۋە مۇناسىۋەتلىك مەھسۇلاتلارنىڭ سۈپىتىنى ئۆستۈرۈپ, كونكرېت مەھسۇلاتلارنى ئۆستۈرىۋاتقاندەك ئوينىماقتا. مەسىلەن, HPMC باشقا HTCMC نىڭ جەڭچىلەشتۈرۈش ئالاھىدىلىكىنى ئۆزگەرتىپ, كراھىنىڭ يېقىلغۇ كۈچىنى ئازايتالايدۇ. , HPMC ئاۋازدىكى نەملىكلەرنىڭ زىيىنىنى ئازايتالايدۇ, بول, بولنىڭ قاتتىقلىقىنى قىسقارتالايدۇ ۋە بولاقنىڭ قېرىپ كېتىشىدىن ئۈنۈملۈك چەكلەيدۇ.

گەرچە HPMC تەرىپىدىن مەلۇم دەرىجىدە ئوچۇق خېرىدار ۋە بولكاغا قارشى تۇرۇش ۋاكالەتچىسى ۋە بولكا قاتارلىقلار قىلىپ ئىشلىتىلىدۇ,, ئىشلەپچىقىرىش خاسلىقىنى, ئىشلەپچىقىرىش خاسلىقىنى, چوڭ تىپتىكى ئىشخانا ۋە ئۇزۇندىن قالالايدۇ. Dear Gum, كاناان گوم قاتارلىق جىنىسلىق كوللودقا سېلىشتۇردى, پۇڭەك ۋە توڭلىمە ۋە توڭلىتىلغان HPIC نىڭ قوللىنىشچانلىرى خېمىرتۇرۇچنىڭ قوللىنىشچانلىرى توڭلىتىلغان بولسۇن ئۇنىڭ ئۈنۈمىگە مۇناسىۋەتلىك مۇناسىۋەتلىك دوكلاتلارنىڭ كەملىكى بار.

1.2ReSearch مەقسىتى ۋە ئەھمىيىتى

ھازىر, باشتىن كەچۈرگەن توڭلىتىنى بىر تەرەپ قىلىش تېخنىكىسى ھازىرلىنىۋاتقان تېخنىكىنىڭ قوللىنىشچانلىقى ۋە چوڭ ئىشلەپچىقىرىش يەنىلا تەرەققىيات باسقۇچىدا. شۇنىڭ بىلەن بىر ۋاقىتتا, مۇزلاپ كەتكەن خېمىرنىڭ ئۆزىدە بەزى كەمتۈكلۈك ۋە كەمتۈكلەر بار. بۇ ئۇنىۋېرسال ئامىللار شۈبھىسىزكى ھەر توڭلىتىلغان خېمىرنى ئىلگىرى سۈرۈشنى چەكلەڭ. يەنە بىر تەرەپتىن, بۇ ئىككى توڭلىتىلغان خېڭنىڭ قوللىنىشچانلىقىنىڭ ياخشى ۋە كەڭ ئىستىققىسىنىڭ زور دەرىجىدە ئېشىشىغا ئېرىشتى, بولۇپمۇ خېلى يېنىكلىكتىكى جۇڭگو سۇنى ئومۇميۈزلۈك گەۋدە قىلىپ, جۇڭگو ئاھالىلىرىنىڭ ئېھتىياجىغا ئېرىشكەن تېخىمۇ كۆپ مەھسۇلاتلارنى بىرلەشتۈرۈشتىن باشلاپ, جۇڭگو ئاھالىلىرىنىڭ چەتئەلدىكى سېتىلىشىنى بىرلەشتۈرۈشتىن مۇھىمراق. خەنزۇچە پېچىنە-پىرەنىكنىڭ ئالاھىدىلىكىگە ئاساسەن, توڭلىتىلغان خېلغەتلىك ھوراننىڭ سۈپىتىنىنى ياخشىلاش, توڭلاتقۇنىڭ ئالاھىدىلىكىگە ئاساسەن توڭلىتىدىغان خېمىرەتنىڭ سۈپىتىنى ئۆستۈش, جۇڭگو پېچىنە-پىرەنىرىنىڭ بىر تەرەپ قىلىش ئالاھىدىلىكىگە ماس كېلىدۇ.

بۇ چوقۇم Enpriset نىڭ جۇڭگو چۆكۈلمىلىرىدىكى مۇناسىۋەتلىك قوللىنىشچان تەتقىقات سەۋەبىدىن يەنىلا كەم بولسا بولىدۇ. شۇڭلاشقا, بۇ تەجرىبەنىڭ مەقسىتى HPMC نىڭ توڭلىتى ۋە توڭلىتىلغان خېمىر ئارقىلىق HPMC ئارقىلىق HPMC ئارقىلىق HPMC ئارقىلىق توڭلىتىلغان خېمىر تەرەپنىڭ ياخشىلىنىشىنى چىقىرىپ, ھورۇن بىر نەچچە ھالكۇللېي خېمىرنى ئېچىش. بۇنىڭدىن باشقا, HPMC خېمىرىن (بۇغداي دېسوغلانچە, كرەت, شاھزات سۇيۇقلۇقى) نىڭ ئۈچ چوڭ تەركىبلىرىگە قوشۇلدى ۋە بۇغداينى ئاقلاش ۋە خۇتەكنىڭ قۇرۇلمىسى ۋە خالشىشى سىستېمىلىق تەسىرى سىستېمىلىق تەتقىقاتى سىستېمىلىق پىلانلانغان. ھەمدە مۇناسىۋەتلىك مېخانىزي خېمىرنىڭ ئۆسۈش ئۇسۇلى ئۈچۈن يېڭى مۇمكىن, چۈنكى, توڭلىگىلى بولىدىغان گازنىڭ يېمەكلىك ئورنىنى ئاشۇرۇش ئۈچۈن يېڭى مۇمكىن, ھەمدە يېمەكلىك دۇنياسىدا HPMC نىڭ ئىشلىتىش ھوقۇقى بولۇپ, توڭلىتىلغان خېمىنى ئوغرىلىق بىلەن ماس ھالدا قوللاشقا ماس كېلىدۇ.

1.3 تەتقىقاتنىڭ ئاساسلىق مەزمۇنى

ئۇ ئادەتتە ئۇ خېغىتىنىڭ كۆپ تەركىبدىكىلەرنىڭ ئالاھىدىلىكى, كۆپ مىقداردىكى يۇمشاق دېتال ۋە كۆپ خىل ھالەتكە ئوخشاش تىپىك يۇمشاق مەسىلە ۋە كۆپ خىل شەكىلدە يۇمشاق يۇمشاق دېتال سىستېمىسىنى ئۆزگەرتتى دەپ قارا رەڭلىك يۇمشاق مەسىلە.

توڭلىتىلغان خېغىر ۋە خۇلەئاسى ۋە خۇسۇسىلىنىشنىڭ قۇرۇلۇشى ۋە توڭلىتىلغان ساقلاش ۋاقتىغا تەسىر كۆرسىتىدۇ, توڭلىتىلغان نۇقالىق مەھسۇلاتلىرى), بۇغدېگر كپۇرگىنىڭ قۇرۇلمىسى ۋە مال-مۈلۈكلىرى ۋە ئېچىلغانلىقى ۋە يېقىشلىق بولغان تىغ ئۇچىنى ئىگىلەيدۇ. يۇقارقى ئويلىنىشنى ئاساس قىلىپ, تۆۋەندىكى تەجرىبىلىك تەجرىبە لايىھىسى بۇ تەتقىقات تېمىسىدا كۆرۈلدى:

1) يېڭى تىپتىكى گىدروگرافىنى تاللاڭ, Heddroyprowyl Methylcelluclse (HPMC) قالايمىقانلىشىپ, YPMC نىڭ قوشۇلما قىممىتى تۆۋەنلىتىلىدۇ (0, 15, 60 كۈن. (0%, توڭڭى توڭلىتىلغان خېمىرنىڭ بىر تەرەپ قىلىش خۇسۇسىيىتىدە HPMC

2) ياخشىلاش مېخانىزمىنىڭ كۆزگە ئايلىنىشى, سۇ كۆلىمى ئۆتۈنۈپ, سۇ دۆلىتى ۋە قاناشنىڭ قۇرۇلمىسى ۋە بۇغداي گوللاندىيە يېغىلغۇنىڭ قۇرۇلمىسى ۋە مال-مۈلۈكلىرى ئوخشىمىغان توڭلىتىش ۋاقىت ۋاقىت شارائىتى ئاستىدا.

3) ياخشىلاش مېخانىزمىنىڭ كۆزگە كۆرۈنەرلىك بولغان تەرەپ, گۆشسىز ساقلانمىلار, گرمۇزلاشتۇرۇش ماھىيىتىنىڭ ئوخشىمىغان HPMC نى, گرمۇشلاشتۇرۇش مۈلكىنىڭ تەسىرى ئوقۇلدى,

4) تەپسىلاتىنىڭ ياخشىلىنىشى, ھايات قېلىش نىسبىتى قاتارلىقلاردىكى نىسبەت, ھاياتنىڭ يېغىش نىسبىتىدىكى ئوخشىمىغان HPMC قوشۇش شارائىتىنىڭ تەسىرىدە ئېچىلغان HPMC قوشۇش شارائىتىنىڭ تەسىرىدە ئېچىلدى.

2-باب I-IPMC نىڭ توڭلىتىلغان خېمىر پىششىقلاپ ئىشلەش خاسلىقى ۋە ھور سۈپىتى

2.1 تونۇشتۇرۇش

ئومۇمەن قىلىپ ئېيتقاندا, ھەق بەرگەن ئۇن ئېچىش ئۈچۈن ئىشلىتىلگەن ماتېرىياللارنىڭ ماتېرىيالى, قوغداش), جاراڭلىق سۇ ياكى ئورگانىك سۇ, ئورگانىك سۇ ياساشلىرى ۋە ئوررىكلىق ۋە ئۆز-ئارا تەسىر كۆرسىتىشتىن كېيىن ياسالغان. ئالاھىدە قۇرۇلما بار مۇقىم ۋە مۇرەككەپ ماتېرىياللار تەرەققىي قىلدى. نۇرغۇنلىغان تەتقىقاتلار خېمىرنىڭ خالتىسى ئەڭ ئاخىرقى مەھسۇلاتنىڭ سۈپىتىگە دۇچ كەلگەنلىكى كۆرسىتىلدى. شۇڭلاشقا, كونكرېت مەھسۇلاتنىڭ مەھسۇلات ياكى ئىشلىتىلىدىغان يېمەكلىك ياكى ئىشلىتىلىدىغان خېمىر تۈزۈش ۋە تېخنىكىسىنى ياخشىلاش ئۈچۈن بىر تەتقىقات يۆنىلىشلىشىش قىلىدۇ. مەھسۇلاتنى پىششىقلاپ ئىشلەش ۋە قوغداشنىڭ خۇسۇسىيىتىنى ياخشىلاش, ياخشىلاش ياكى ياخشىلاش مۇھىم تەتقىقات مەسىلەمۇ بولىدۇ.

تونۇشتۇرۇشتا HPMC نى خېما سىستېمىغا قوشقان ۋە خېمىرلاش, كۇڭتۇڭ, شىڭولوگىيە قاتارلىقلارنىڭ تەسىرىنى تەكشۈرۈش ۋە ئاخىرقى مەھسۇلات سۈپىتىنىڭ تەسىرىدە ئىككى خىل يېپىشقاق مۇناسىۋەتلىك تەتقىقاتلارنى تەكشۈرۈش.

شۇڭلاشقا, بۇ تەجرىبە لايىھىسى ئاساسلىقى ئىككى تەرەپتىن ئېلىپ بېرىلدى: HPMM نىڭ توڭگېن خېبرەم سىستېمىسى ۋە پارتلاش ئىقتىدارىغا ئۇچرىغان.

2.2 تەجرىبە ماتېرىياللىرى ۋە ئۇسۇللىرى

2.2.1 تەجرىبە ماتېرىياللىرى

Zhongyu بۇغدۇ بۇغداي بىنسۇج بىناخۇ? پەرىشتە ئاكتىپ قۇرغۋاق شەرىئال شەربىتى HPMC (Methyl نىڭ ئورنىنى ئېلىش نىسبىتى% 28.% 8,% 5) ئالدرويپا (شياڭگاڭ) خىمىيىلىك پۇلنى قايتۇرۇش شىركىتىنى% 7. بۇ تەجرىبىدە ئىشلىتىلىدىغان بارلىق خىمىيىلىك ئىجارە ئاجرىتىلغان بارلىق سىناق دەرىجىسى

2.2.2 تەجرىبە ئەسكىرى ۋە ئۈسكۈنىلىرى

چالغۇ ۋە ئۈسكۈنىلەرنىڭ ئىسمى

BPS. 500 ئادەم توختىماي تېمپېراتۇرا ۋە نەملىك ساندۇق

TA-RTSTAL STANCE SPACKE SILLISS TESTER

BSAL24S4s ئېلېكترونلۇق تەھلىل قىلىش تەڭپۇڭلۇقى

Dhg. 9070a پارتىلاش ئوچاق

Sm. 986s خېمىر ئارىلاشتۇرۇلغان

C21. Kt2134 Incuction couter

پاراشوك مېتىر. E

كېڭەيتىش. E

R3 ئايلىق رېشاتكىسى

Q200 پەرقلىق سىكانىرلاش ئىسسىقلىق ئۆيى

Fd. 1b. 50 ۋاكۇئۇمنى توڭلىتىدۇ

SX2.40.10 مۇپكە يەتتى

KJېلېتېر TM 8400 ئاپتوماتىك كىيەلەلگەن ئانتروگېن ئانالىزچىسى

ئىشلەپچىقارغۇچى

شاڭخەي جخېڭ ئىلمىي ئىلمىي ۋاگېن چەكلىك شىركىتى چەكلىك.

Crabic mice use, uk

Sartorius, گېرمانىيە

شاڭخەي جخېڭ ئىلمىي ئىلمىي ۋاگېن چەكلىك شىركىتى چەكلىك.

ئەڭ يۇقىرى ئاشخانا ئېلېكتر ئۈسكۈنىلىرى تېخنىكا چەكلىك شىركىتى.

گۇاڭدۇڭ سەلادلىقلار تۇرمۇش ئېلېكتر ئۈسكۈنىلىرى ئىشلەپچىقىرىش C., LTD.

Briberder, گېرمانىيە

Briberder, گېرمانىيە

ئامېرىكا TA شىركىتى

ئامېرىكا TA شىركىتى

بېيجىڭ بويۇم بوڭ تەجرىبە ئەسكىرى چەكلىك شىركىتى.

خۇاڭ شى خېڭ فېڭ فېڭ داۋالاش ئۈسكۈنىلىرى چەكلىك شىركىتى LTD.

دانىش تاشقا

2.2.3 تەجرىبە ئۇسۇلى

2.2.3.1 ئۇننىڭ ئاساسىي زاپچاسلىرىنى بەلگىلەش

GB 50093.2010, GB 5009.510, Gb / T.99.2008, بۇغداي ئۇنلىقى - نەملىك, ئاقسىل, كاۋاپ ۋە كۈل مەزمۇن بولۇشنىڭ ئاساسىي تەركىبىي قىسمى.

2.2.3.2 گۈللۈكنىڭ پاخۇشىنى بەلگىلەش

پايدىلىنىش ئۇسۇلى GB / T 14614.2006 خېمىرنىڭ خېمىرتۇرۇلۇشىنىڭ دەرىجىسىنى بەلگىلەش.

2.2.3.3 جىددىيلىك خۇسۇسىيىتىنى بەلگىلەش

GB / T نىڭ GB / t 14615.2006 غا ئاساسەن جىددىيلىك خۇسۇسىيىتىنى بەلگىلەش.

2.2.3.4 توڭلىتىلغان خېمىر

GB / T 17320.1998 نىڭ قىچا ياساش جەريانىنى كۆرۈڭ. ئېغىرلىقىڭىز بوغۇزىنى ياخشى قاچىلاش, خېمىر بوغۇزىقى بوغۇزىقىدىكى رولنى ئېگىز ئارىلاشتۇرۇپ, سائەت 24 مىنۇت 180G / بىر بەت شەكلىگە سىلىندىر شەكىلگە كىرىپ, ئۇنى Ziplick بىلەن پېچەتلەش, ھەمدە% 0.5 (% 15 ° C (% 15 ° C (1 كۈنلۈك توڭلىتىلغان ساقلاش) ئۆزگەردى كونترول تەجرىبە گۇرۇپپىسى.

2.2.3.5 رېئولوگىيەلىك خۇسۇسىيەتنى بەلگىلەش

مۇناسىپ توڭلىتىش ۋاقتىدىن كېيىن تېرىلىك ئەۋرىشكە تەييارلاڭ, ئۇلارنى توڭلاتقۇغا سېلىڭ, ئاندىن ئۇلارنى ئۆي تېمپېراتۇرىسىدا پۈتۈنلەي ئېرىپ كەتتى. ئەۋرىشكىسىنى پىششىقلاپ ئىشلەش ئۇسۇلى تەجرىبە) مۇرەككەپ قىسىم قىسمىمۇ ئىشلىتىلىدۇ.

قىسمەن ئېرىتىلگەن خېمىرنىڭ مەركىزى (تەخمىنەن 2 گرام) نىڭ ئەۋرىشكىسى ياكى رېمونت قىلغۇچىنىڭ ئاستى تەخسىگە قويۇلغان. بىرىنچىدىن, ئەۋرىشكى ھەرىكەتچان بېسىملىق سايىلەپ, ئەۋرىشكە ئېلىپ بېرىلىپ قالدى. كونكرېت تەجرىبە پارچىلىرى تۆۋەندىكىچە: 40 مىللىمېتىردا 40 مىللىمېتىر ئىشلىتىلگەن: پەرقلىق بولۇپ, تېمپېراتۇرا 100 ° ° ° كىمۇ يەتكەن, سايىلەش دائىرىسى 25.01 بولسا. 100%, ئەۋرىشكە دەم ئېلىش ۋاقتى 10 مىنۇت, چاستوتىسى 1Hz غا تەڭشەلدى. سىناق قىلىنغان ئەۋرىشكە (LVR) STROCKED SPORDS نىڭ (LVR) بېسىملىق سىكانىرلاش ئارقىلىق بېكىتىلدى. ئاندىن, ئەۋرىشكا ھەرىكەتچان چاستوتا ئورالغان بولۇپ, كونكرېت ھەرپلەر تۆۋەندىكىچە, جىددىيلىشىپ, نىسبىتى% 0.5 0.5.% 0.5.% 0.5 بولدى. بەش سانلىق مەلۇمات نۇقتىسى (پىلان) چاستوتا (سىزىقلىق ھالەت) نىڭ ھەر 10 ھەسەل سىرتىدىكى ھەر 10 ھەسسە كۆپەيتىش ئۈچۈن رېئوگىيەلىك (سىزىقلىق ھالەت). ھەر بىر قىسقۇچنىڭ سۈزۈلمىگەندىن كېيىن, ئارتۇق ئەۋرىشكە تىغ بىلەن تەۋرىنىشتى, ئاستا-ئاستا پاراق, پاراشوتتىن قەۋەتنىڭ چېتى ئەۋرىشكىنىڭ چېتى سۇس قويۇلغان بولۇپ, تەجرىبە مەزگىلىدە سۇ يوقىتىۋېتىشىنىڭ ئالدىنى ئالدى. ھەر بىر ئەۋرىشكى ئۈچ قېتىم تەكرارلاندى.

2.2.3.6 نىڭ مەزمۇنى (توڭلىغىلى بولىدىغان سۇنىڭ مەزمۇنى) خېمىردىكى CF ئىچكى ئىرادىسى)

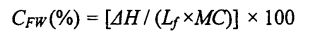

تولۇق ئېرىتىلغان خېغىرىنىڭ مەركىزى قىسمىدىن تەخمىنەن 15 مىللىگىرام ئەۋرىشكە پېچىنە (سۇيۇق ئەۋجەللىك ئەۋزەللىكىگە ماس كېلىدۇ), ئۇنى پەرقلىك ساناقلىق Halorytry (DSC) بىلەن ئۆلچە. كونكرېت پروگرامما پارامېتىرلىرى بېكىتىلدى. تۆۋەندىكىچە: ئالدى بىلەن 20 ° C دىن ئېشىپ, ئاندىن 10 مىنۇت ساقلىغاندا, ئاخىرى 25 مىنۇت ساقلىغاندا, پاكلىق گازى كېيىن 25 كىلوگرام ئۆرلەڭ (N2) ۋە ئېقىمى 50 مىللىمېتىر كېلىدۇ. پايدىلىنىش ماتېرىيالى سۈپىتىدە دەرىجىگە ئايرىلغان قۇرۇق ئاليۇمىننى ئىشلىتىپ, DSC ئەگرى سىزىقلىق ئانالىزچىدىن 2000-بەت ۋە مۇز Entathlpy (بىر كۈن) مۇزلۇقنىڭ سېتىلىشى 0 ° C قاتارلىقلارنى بىرلەشتۈردى. توڭلىتىش سۇ تەركىبى (CFW) تۆۋەندىكى فورمۇلا تەرىپىدىن ھېسابلىنىدۇ [85.86]:

بۇنىڭ ئىچىدە نەملىكنىڭ ھۈجاپىسى دائىرىسىگە ۋەكىللىك قىلىدۇ, قىممىتى 334 JU دان. MC (ئومۇمىي نەملىك مىقدارى) خېمىردىكى ئومۇمىي نەملىك مىقدارىغا ۋەكىللىك قىلىدۇ (GB 50093.2010T78 بىلەن ئۆلچىنىدۇ]). ھەر بىر ئەۋرىشكى ئۈچ قېتىم تەكرارلاندى.

2.2.3.7 نان ئىشلەپچىقىرىشى

مۇناسىپ جاھىللىقتىن كېيىن, توڭلىتىلغان خېمىر سىرتقا چىققاندىن كېيىن, ئالدى بىلەن 4 ° C توڭلاتقۇدا بولۇپ, ئاندىن ئۆي تېمىسىنى پۈتۈنلەي ئېرىدى. خېمىنىڭ بىر قىسمىغا يېقىنلاشقان گرامنى شەكىللەندۈردى, ئاندىن ئۇنى توختىماي تېمپېراتۇرا ۋە نەملىك ساندۇققا بېرىڭ, ھەمدە ئۇنى 30 ° C ۋە نىسپىي نۇقسانكىسى 30 گرام. ئىسپاتلانغاندىن كېيىن, ھور 20 مىنۇت, ئاندىن ئۆينىڭ تېمپېراتۇرىسىدا 1 سائەت سوۋۇتۇش.

2.2.3.8 ھورنىڭ سۈپىتىنى باھالاش

(1) ھوردىن كەلگەن ناننىڭ كونكرېت مىقدارىنى بەلگىلەش

GB / T 20981.2007 [871 [871) ھوردىن ياسالغان بىر بورنىڭ ئاۋازى (M) نىڭ ئاۋازى (خىزمەت) ھەر بىر ئەۋرىشكە ئۈچ قېتىم كۆپەيتىلدى.

ھورلانغان بولكا ئالاھىدە ھەجىم (cm3 / g) = ھوردا نان (CM3) / ھور (cm3) / ھور (GM)

(2) ھور دەۋرىدىكى پارتلاش خاسلىقى

SIM, نۇتۇق دۇنياۋى, چېڭ (2011) [8] [ھازىرقى ئۆزگەرتىشلەر بىلەن) [88] [88] [88] [88] [88] [88] [88] [88] [ھازىرقى ئۆزگەرتىشلەر. ھوردىن 20x 20 x 20 mn'13 يادرولۇق بولكا پارلامېنت ئەزالىرىنىڭ مەركىزى ناندىن ياسالغان كونكرېت پارامېتىرلار: تەكشۈرۈش نىسبىتى PM / 100 بولۇپ, ئوتتۇرا ئۆلچەمدىن كېيىنكىت مىقدارى 1 MM / S. ھەر بىر ئەۋرىشكىدىن 6 قېتىم تەكرارلاندى.

2.2.3.9 سانلىق مەلۇمات بىر تەرەپ قىلىش

باشقىچە بەلگىلىمە چىقىرىلمىسا, باشقىچە بەلگىلەنگەن بولسا, تەجرىبە نەتىجىسى ئاساسەن (مەنىلىك) ± ئۆلچەملىك ياتلىشىش (ئۆلچەملىك ياتلىشىش) دەپ قارالدى. Spss StarkICIS 19 ئېغىزىنى تەھلىل قىلىشقا ئىشلىتىلگەن (ئوخشىماسلىق, ئارا ۋە ئىنجىل مۇھىتى). 8.0 نى ئىشلىتىپ مۇناسىۋەتلىك جەدۋەللەرنى سىزىڭ.

2.3 تەجرىبە نەتىجىسى ۋە مۇنازىرە

2.3.1 بۇغداي ئۇننىڭ ئاساسىي تەركىبى

بۇغداي ئۇننىڭ باشلانغۇچ تەركىبلىرىنىڭ باشلانغۇچ تەركىبلىرى

2.3.2 I-IPMC نىڭ ۋاشىنگېردىكى ھادىسەنىڭ تەسىرىگە قوشۇلۇشنىڭ تەسىرى

2.2 جەدۋەلدە كۆرسىتىلگەندەك, HPM نىڭ كۆپىيىشى كۆرۈنەرلىك بولغاندا, خېمىر ئۆسۈش نىسبىتى% 5.60 ئېشىپ,% 2 HPM SoGh) نى قوشىدۇ. بۇنىڭدىن باشقا, HPMC نىڭ قوشۇلۇشىدىن كېيىنكى مەركىزى 5.2 مىنۇت (قۇرۇقلۇق) دىن 12.2 مىنۇت (% 2 HPMC) نى كۆپەيتىڭ. قانداقلا بولمىسۇن, HPMC NO سىنىڭ% 55.0M لىق بولۇپ, قۇرۇق خېمىرنىڭ ئاجىزلىنىشى ئومۇمىي جەھەتتىن 55.0 ۋە ئاجىزلىقتا بولۇپ, ئايرىم-ئايرىم ھالدا% 18.57 تۆۋەنلىگەن.

چۈنكى HPMC نىڭ كۈچلۈك سۇنى ساقلاپ قېلىش ۋە سۇ ساقلاش ۋە سۇ ئېچىش. خېلى خان جەمەتى كۆتۈرۈش نىسبىتى تېخىمۇ ياخشى بولىدۇ. خېغىرى ئېچىنىشلىق ۋاقىتخان تۇغۇپ, HPMC توقۇلغان ۋاقىتنى كونترول قىلىدۇ خېغىرىنىڭ شەكىللىنىشى. خېمىردەك مۇقىملىق ۋاقتى 500 فۇنىڭ ئۈستىگە چىقىرىلغان ۋاقتى, ئۇ ئەينىزامىغا يەتكەندە خېيى ۋە نىسبەت بويىچە خېيى, ئۇ ئاجىزلىق دەرىجىسى يۇقىرىدىن ھالقىپ كېتىش دەرىجىسى خېمىر كېلىدىغان ۋە ئاخىرقى ئىزچىللىق بىلەن HPMC تەرىپىدىن خېمىرتۇرۇلىنىڭ كۆرسىتىلىشىدە, HPMC نىڭ خېمىلدىكى مۇقىملىقىنى مۇقىملاشتۇرۇپ بولغانلىقتىن, HUGM نى ئاجىزلاش ۋاقتى لەر ۋە HUGM نىڭ مۇقىملىقى, HPMC نىڭ مۇقىملىقى, بۇ نەتىجىلەر Hought ۋە Hars نىڭ تەتقىقات نەتىجىسىنى ئۆزگەرتكەنلىكىنى كۆرسىتىپ بېرىدۇ, بۇ نەتىجىلەر

ئەسكەرتىش: ئوخشاش ئىستوندىكى ئوخشىمىغان دەرىجىدىكى دەرىجىدىن تاشقىرى خەت (P <0.05)

2.3.3 HPMC نىڭ خېمىر تىكىش خۇسۇسىيىتىدىن باشقا

خېمىردىكى بىرلىككە كەلگەن خۇسۇسىيەت دەلىل-ئىسپات, جىددىيلەشتۈرۈش, جىددىي قارشىلىق ۋە سوزۇلۇش نىسبىتىنىمۇ ياخشى ئەكس ئەتتۈرەلەيدۇ. خېمىردىكى بىرلىككە كەلگەن خۇسۇسىي خۇسۇسىيسى بولغاچقا, خېمىرنى كېڭەيتىش رولىدىكى ئۇزۇنلۇقتىكى كەڭلىكتىكى چوڭ چىراغنىڭ كېڭەيتىلمىسىغا خاس تەسەللىلەشنى بەلگىلەيدۇ [921]. ۋاقىت دېمىسى, سىمىس (1987) [93] ئەتراپتىكى بىر چەمبىرەك زەنجىرىنىڭ ئارىلىقى زەنجىرى ئارىلىقىدا ئىككىلەمچى زەنجىرسىمان زەنجىرگە باغلىق. مولېكۇلا زەنجىرىنىڭ ئۆزگىرىشى بىر قەدەر تۆۋەن, مولېكۇلا زەنجىرنىڭ بۇزۇلۇشى يېتەرلىك بولىغا قويۇشقا, مولېكۇلي زەنجىرنىڭ كېڭەيتىش ئۇزۇنلۇقىنىڭ تېز بولۇشىمۇ قىسقا. مولېكۇلي زەنجىرىنىڭ ئۆزگىرىشى نىسبىتى پەقەت مولېكۇل ھاكىمىيەت زەنجىرسىمان زەنجىرسىمان زەنجىرسىمان زايوم زايوكىنىڭ خەۋەرلىشىشتۈرۈشىگە كاپالەتلىك قىلالايدۇ, مولىك زاپىسى يۈز بەرگىلى بولمايدۇ, كۆپ ئىقتىدارلىق پۇلنى كۆپەيتىشكە كاپالەتلىك قىلالايدۇ. شۇڭلاشقا, گلتىرى ئاقسىل زەنجىرنىڭ چىقىم زەنجىسىنىڭ تارقىلىش ۋە ئارىسىنىڭ ئۆزگىرىشى ۋە كېڭەيتىش خاھىشىسىنىڭ ئورنى بولىماقتا, خېڭنىڭ جىددىيلۈك دەرىجىسىگە ئېلىپ كىرىش [92].

جەدۋەل 2.3 ئوخشىمىغان مىقداردىكى HPMC نىڭ تەسىرى (O قاتارلىق% 1.5 ۋە% 1) ۋە ئوخشىمىغان ئىسپاتلار 1'9 (45 مىنۇت, 95 مىنۇت, 95 مىنۇت, بۇزۇلۇش, ئەڭ يۇقىرى چەككە سېلىشتۇرۇش, ئەڭ ئۇزۇن چەك, يۇقىرى ئۆرلەش نىسبىتى ۋە مەركەزلىك نىسبىتى ۋە مەركەزلىك نىسبەت بويىچە). تەجرىبە نەتىجىسىدە كۆرسىتىلىشىچە, بارلىق خېمىر ئەۋزەللىكنىڭ ئىسپاتىنىڭ ئۇزارتىلىشى بىلەن ئازىيىشى بىلەن ئازىيىشى بىلەن ئۇزارتىلىدىغان كېڭەيتىلىش ۋاقتىنىڭ ئىسمىنى ئۇزارتىش ۋاقتى بىلەن ئاشىدىكەن. ئېنېرگىيە قىممىتى 0 دىن 90 مىنۇتقىچە, باشقا% 1 لىك يۇقىرى ئۆرلەش نىسبىتى تەدرىجىي بار ئاستا, بارلىق يۆتەلنىڭ ئېنېرگىيە قىممىتى تەدرىجىي ئاشتى. كۆرۈنەرلىك ئۆزگىرىش بولمىدى. بۇ كۆرسىتىپ, تەكشۈرۈش ۋاقتى 90 مىنۇت بولغاندا, خېمىرنىڭ تور قۇرۇلمىسى (مولېكۇلا زەنجىرى ئارىسىدا يۈزلىنىش) پۈتۈنلەي شەكىللەنگەن. شۇڭلاشقا, ئىسپاتلاشتۇرۇش تېخىمۇ كېڭەيتكەن, ئېنېرگىيە قىممىتىدە كۆرۈنەرلىك پەرق يوق. شۇنىڭ بىلەن بىر ۋاقىتتا, بۇ يەنە خېمىرنىڭ ئىسپاتلانغان ۋاقتىنى بەلگىلەشكە بولىدۇ. مولېكۇلا زەنجىرىنىڭ سابىق نەتىجىسى بولۇپ, مولېكۇلا زەنجىرىنىڭ ئارىسىدىكى ئۇزۇنلۇق زەنجىرلىرى قۇرۇلدى, شۇڭا جىددىيلىك قارشىلىق ۋە ئەڭ يۇقىرى نازارەت قىلىش ئىقتىدارى تەدرىجىي كۈچى تەدرىجىي كۈچىيىدۇ. شۇنىڭ بىلەن بىر ۋاقىتتا, مولېكۇلياكات زەنجىرىنىڭ چېكى ئۆزگىرىشىدە, مولېكۇل ھاكىرى زەنجىرى ئوتتۇرىسىدىكى چاستورلۇق زەنئىنىڭ ئوتتۇرىسىدا يېپىق ئۆرلەش نىسبىتى تۆۋەنلىدى, بۇلارنىڭ ئىسپاتلانغان ئۇزاق ئۆتۈشىنىڭ ھەددىدىن زىيادە ئۇزارتشىنى ئازايتقىلى بولىدۇ. جىددىيلىك قارشىلىق / ئەڭ يۇقىرى ئىجادىيەتكە قارشى تۇرۇش كۈچى, ئۇزۇنلۇقتا كېڭىيىدۇ ۋە ئۇزۇنلۇقتىكى جىددىيلىكنىڭ كۆپىيىشى ھېسابلانغان.

قانداقلا بولمىسۇن, HPMC نىڭ قايتا ئورنىدىن باشلاپ يۇقىرىدىكى يۈزلىنىشنى ئۈنۈملۈك كۆرسىتىپ, خېمىرنىڭ ماسلىشچان خاسلىقىنى ئۆزگەرتىدۇ. HPMC Leca نىڭ كۆپىيىشىگە ئەگىشىپ, بىر قەدەر كەڭ كۆلەملىك, ئېگىزلىكىنىڭ ئەڭ داڭلىق بولغان مەبلەغ قىممىتى مۇناسىپمۇ مۇناسىپ تۆۋەنلىگەن, ئۇزۇن ئۆتمەيلا ئۆرلىگەن. كونكرېت قىلىپ ئېيتقاندا, ۋاقىت تەكشۈرۈش ۋاقتى 45 مىنۇلغا بولغاندا, ئۇلۇتنىڭ قۇچىقىنىڭ كۆپىيىشىدە, 148.20-نومۇر), 120.80 ±% 1.20.20-a: 6.58

J (% 2 HPMC قوشۇلدى). شۇنىڭ بىلەن بىر ۋاقىتتا, ھويلىنىڭ Ra: 3918 دىن تۆۋەنلىتىلگەن. قانداقلا بولمىسۇن, خېفنىڭ تېرىدى 154.75 + 7.507 مىچى (FPLANT% 0.5 M دىيۇم), 1625 مىنۇت قوشقان), ۋە 1 67.20-a. HLutuen ئاقلىنولىنىڭ شېخىليات زەنجىرىنىڭ ئۆسۈشى بىلەن ئۇ توختىماي ھەرىكەتلەندۈرگۈچ كۈچنىڭ ئۆسۈشى بىلەن ئۇنى تەسىر كۆرسىتىدۇ, بۇ ئىتنىڭ ئۇزۇنلۇق خۇسۇسىيىتىنى ئۆستۈرىدۇ ھەمدە خېمىرنىڭ ئارتۇقچىلىقىدىن ئۆتىدۇ, بۇ سۈپەتكە تەسىر كۆرسىتىدۇ (مەسىلەن, ئاخىرقى مەھسۇلاتنىڭ كونكرېت ھەجىمى, تېكىست).

2.3.4 HPMC قوشۇلۇشى ۋە خېمىرنىڭ رىياسەتلىك خۇسۇسىيىتىدىكى ساقلاش ۋاقتى

خېمىرالىق ئادەتنىڭ مۇھىم خۇسۇسىيىتىنىڭ مۇھىم كۆزلىرىنى مۇرەككەپلىك قىلىش, مۇقىملىق ۋە بىر تەرەپ قىلىش ئالاھىدىلىكى, پىششىقلاپ ئىشلەش ۋە ساقلاشتىكى قاناتلارنىڭ ئۆزگىرىشى سىستېمىلىق ئىشلىتىلىشىگە سىستېما.

توڭلىتىلغان خېمىرنىڭ رىياسەتچىسىدىن ئايرىلغان

2.1-رەسىم 01-رەسىم 0 كۈن ساقلاش لايىھىسى (Elasicick, G »(Viscus Modulus, g») نىڭ ئۆزگىرىشىدا, G "خېمىرنىڭ ئۆزگىرىشى كۆرۈنەرلىك تۆۋەنلەپ, كىرىدۇ, ئۇنىڭ ئۆزگىرىشى بىر قەدەر كىچىك بولۇپ,. بۇ بەلكىم ھەمبىرەك تور قۇرۇلمىسىنىڭ تور قۇرۇلمىسىنىڭ مۇز قۇرۇلمىسى بىلەن بولغان بولۇپ, توڭلىتىش كۈچىنى تۆۋەنلىتىدۇ,, قۇرۇلما خاراكتېرلىك كۈچنى تۆۋەنلىتىدۇ, شۇڭا ئېلاسادىك مۇتسىياسىنى كۆرۈنەرلىك تۆۋەنلىتىدۇ. قانداقلا بولمىسۇن, HPMC دىن باشقا, G ئاستا-ئاستا ئۆزگىرىشى بىلەن. بولۇپمۇ, HPMC نىڭ قوشۇلما قىممىتى% 2 بولغان بولسا, G 'نىڭ ئۆزگىرىشى ئەڭ كىچىك ئىدى. بۇ كۆرسىتەلمەكتە HPMC مۇز خرۇستال شەكىللىنىشىنى ئۈنۈملۈك چەكلەپ, مۇز خرۇستال چوڭلۇقىدىكى ئېشىش سۈرئىتىنى ئازايتالايدۇ ھەمدە خېمىر قۇرۇلمىنىڭ بۇزۇلۇشىنى ئازايتالايدۇ ۋە خېفنىڭ قۇرۇلمىسى يارىلىنىشىنى كەلتۈرۈپ چىقىرىدىغانلىقىنى ۋە خېمىرنى ساقلاپ قالىدۇ. ئۇنىڭدىن باشقا, خېمىرنىڭ قىممىتى ھۆل گللۇلې خېغىنىڭ ھۆل گلۇمۇ خېمىرىنىڭكىدىن كۆپ, چۈنكى چىڭ تۇرغانلىقى ئۈچۈن ئاساسلىقى گللا تورى قۇرۇلمىسىغا تاپقىلى بولىدۇ. ئۇ ئارتۇقچە تور قۇرۇلمىسىغا ساقلاپ قېلىشقا توغرا كېلىدۇ. ئۇ ئارتۇقچە تور قۇرۇلمىسىنى ساقلاپ قېلىندى.

FPMC قوشۇلۇشى ۋە توڭلىتىلغان سۇ مەزمۇنىدا توڭلىتىلغان سۇ مەزمۇنى (ئىگىدارچىلىق قىلىدىغان سۇ مەزمۇنى)

خېمىكىنىڭ بارلىق نەسلىنىشىسى, مەلۇم تۆۋەن تېمپېراتۇرا شەكىللەندۈرەلمەيدۇ, بۇ بولۇپ, نەملىك قاتارلىق نەملىكە (ھەقسىز ئاق, چەكلەيدۇ) ۋە ئۇنىڭ مۇھىتىغا مۇناسىۋەتلىك. توڭلاتقۇ سۇ تۆۋەن تېمپېراتۇرىدا مۇز كىرىستالنى شەكىللەندۈرىدۇ. توڭلىغىلى بولىدىغان سۇنىڭ مىقدارىغا بىۋاسىتە تەسىر كۆرسىتىدىغان, چوڭلۇق ۋە تارقىتىشنىڭ ئۆزگىرىشىگە بىۋاسىتە تەسىر كۆرسىتىدۇ. بۇنىڭدىن باشقا, توڭلاتقى بولىدىغان سۇ تەركىبى مۇھىت ئۆزگىرىشلىرىنىڭ تەسىرىگە ئۇچرىغان, مەسىلەن مۇھىت ئاستى ساقلاش ۋاقتىنىڭ كېڭەيتىلىشى, ساقلاش ساقلاش تېمپامىتكىنىڭ خاتاغ, ساقلاش سىستېمىسى ۋە ماتېرىيال سىستېمىسى قۇرۇلمىسى ۋە تۈرلۈك ساقلاش ۋاقتىنى ئاشۇرۇش. توڭلىتىلغان خېغىرى HPMC نى قوشتى, چمۇش ساقلاش ۋاقتىغا قارىغاندا, CMINECON نىڭ ئېچىلىڭ, 32.48% (توڭلىتىلغان ساقلاش 09.14 (توڭلىتىلغان ساقلاش 0 دە% 0.3.1s (توڭلىتىلغان ساقلاش 0 كۈن). زالىم 60 كۈن), ئېشىش نىسبىتى% 2047 بولدى. قانداقلا بولمىسۇن, 60 كۈنلۈك ساقلاشتىن كېيىن, HpmC نىڭ ئۆسۈشى, CFC نىڭ ئېشىش سۈرئىتىدىن ئاشتى, ئۇنىڭدىن% 18.41,% 13.41,% 13.48). شۇنىڭ بىلەن بىر ۋاقىتتا, HPMC يەنە بىرىنىڭ مىقدارىنىڭ ئېشىشىغا ماس كېلىدۇ, 32.48A-0.32% (IPMC) غا 31.73 ± 0.20%. . يېتىشتۈرۈش چارىسى, قىستۇرغىلى بولىدىغان ھالەتنى ئەسلىگە كەلتۈرۈش جەريانىدا, شۇڭا ئاستا بولگىلى بولمايدىغان سۇنىڭ بىر قىسمى توڭلاتقى بولىدىغان سۇغا ئايلىنىدۇ. قانداقلا بولمىسۇن, HPMC مۇز خرۇستالنىڭ شەكىللىنىشى ۋە ئېشىشىنى ئۈنۈملۈك چەكلىيالايدۇ ھەمدە خېمىر قۇرۇلمىسىنىڭ مۇقىملىقىنى قوغدىيالايدۇ, شۇنىڭ بىلەن توسۇلى بولغان سۇ تەركىبىنىڭ ئېشىشىنى ئۈنۈملۈك چەكلەش. بۇ تېرىنىڭ قانۇنىدىكى يۇمىلاق شەكىللىك ھۆللۈك قانۇنىدىكى قانۇنىغا ماس كېلىدۇ, ئەمما تېرىنىڭ تېخىمۇ چولپاندا بار, CFW قىممىتى ھۆل گىلەم ئۇفورغان (جەدۋەل) قىممىتىدىن كىچىك.

2.3.6 لىموم قوشۇلۇشى ۋە ھورلانغان ناننىڭ سۈپىتى

2.3.6.1 HPMC قوشۇلۇشىنىڭ تەسىرى ۋە پالغۇشنىڭ ھورۇنلۇق ۋاقتى

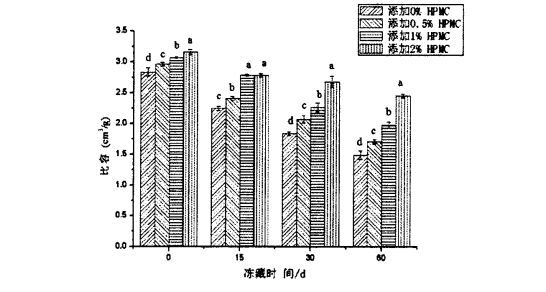

ھورلانغان ناننىڭ كونكرېت مىقدارى ھورلانغان ناننىڭ كۆرۈنۈشى ۋە سەزگۈسىنىڭ سۈپىتىنى تېخىمۇ ئۆچ ئالالايدۇ. ھور ناننىڭ كونكرېت مىقدارى, ئوخشاش سۈپەتتىكى پار, ئىمزالانغان نان ۋە كونكرېت ئىمتىمنىڭ تاشقى كۆرۈنۈشى تاشقى كۆرۈنۈشى, رەڭ, رەڭ ۋە سۆرەش ۋە سەزگۈنى ساقلاشقا تەسىر كۆرسىتىدۇ. ئومۇمەن قىلىپ ئېيتقاندا, چوڭراق ھورلار بىلەن ھورۇنلار بار ئىستېمالچىلار بىلەن تېخىمۇ كۆپ تەسىرلىك.

IPMC رادىئوسىنىڭ 2.2 نىڭ ئۈنۈمى ۋە يېڭى ھەجىمنىڭ ئالاھىدە مىقدارىنىڭ مۇقەپلەندى

ھورلانغان ناننىڭ كونكرېت مىقدارى ھورلانغان ناننىڭ كۆرۈنۈشى ۋە سەزگۈسىنىڭ سۈپىتىنى تېخىمۇ ئۆچ ئالالايدۇ. ھور ناننىڭ كونكرېت مىقدارى, ئوخشاش سۈپەتتىكى پار, ئىمزالانغان نان ۋە كونكرېت ئىمتىمنىڭ تاشقى كۆرۈنۈشى تاشقى كۆرۈنۈشى, رەڭ, رەڭ ۋە سۆرەش ۋە سەزگۈنى ساقلاشقا تەسىر كۆرسىتىدۇ. ئومۇمەن قىلىپ ئېيتقاندا, چوڭراق ھورلار بىلەن ھورۇنلار بار ئىستېمالچىلار بىلەن تېخىمۇ كۆپ تەسىرلىك.

قانداقلا بولمىسۇن, توڭلىتىلغان خېۋىرىڭدىن ياسالغان پارنىلغان ناننىڭ توڭلىتىلغان ساقلاش ۋاقتىنى ئۇزارتىشنىڭ كونكرېت مىقدارى بىلەن ئازايدى. بۇنىڭ ئىچىدە, توڭلىتىلغان خېمىردىن HPMC نى قوشماي, توڭلىتىلغان ھالقا 2.835 ± 0.064 CM3 / G (توڭلىتىلغان ساقلاش). 0 كۈن) 1.495 ± 0.070 ± 0.070 CM3 / G (تولغاق ساقلاش 60 كۈن) توڭلىتىلغان ھالغىچە, توڭلىتىلغان ھالقانىڭ كونكرېت مىقدارى% 2.1660 ± 0.041 / G دىن 2.160 ± 0.041 cm3 / g. 451 ± 0.033 cm3 / g شۇڭلاشقا, توڭلىتىلغان خېمىر قوشۇلغان ھورلانغان ھوردىنىڭ كونكرېت مىقدارى. ھور ناننىڭ كونكرېت مىقدارىلىرى سېپىل نانلار پائالىيىتى (فېرمېماتىكا گاز ئىشلەپچىقىرىش پائالىيىتى) بولۇپ, ئۇ ئەڭ ئاخىرقى مەھسۇلاتنىڭ كونكرېت مىقدارىغا نىسبەتەن ئوتتۇراھال تەبىئىي گاز چىقىرىش ئىقتىدارى [96'9 نەقىل ئېلىنغان. تومۇردىكى تور قۇرۇشنىڭ نەتىجىسى ئېچىلىپ, خېمىلىك تور قۇرۇلمىسىنىڭ تومۇر, توڭلىتىش دەرىجىسى بۇزۇلغان بولۇپ, توڭلىتىش ۋاقتىنى ئۇزارتىش بىلەن كۈچەيتىلىدۇ. بۇ جەرياندا ئۇنىڭ گاز ساقلاش ئىقتىدارى نامرات, بۇ ئۆز نۆۋىتىدە پارنىسى ناننىڭ كونكرېت مىقدارىنىڭ تۆۋەنلىشىنى كەلتۈرۈپ چىقىرىدۇ. قانداقلا بولمىسۇن, HPMC نىڭ ھاۋا تەڭشىگۈچنىڭ قوشۇمچە ھوقۇقىنى تېخىمۇ ياخشى قوغدىالايدۇ, شۇنداق بولغاندا O. HTo C. Lup نىڭ 60-قېتىم ئۆسۈشى تېخىمۇ ياخشى, مۇناسىپ چۈشنىڭ كونكرېت مىقدارى تەدرىجىي تۆۋەنلەيدۇ.

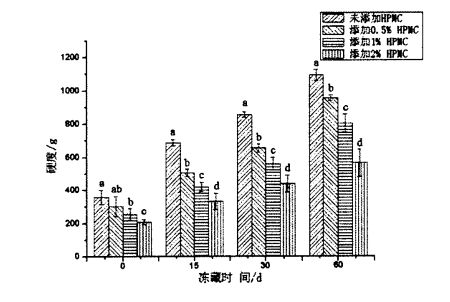

2.3.6.2 HPMC قوشۇلۇش نىسبىتى ۋە تولغان ناننىڭ پۇرىقى

TPA (سالامەتلىك ئالاقە تەھلىللىرى) فىزىكىلىق مۈلۈك تەكشۈرتۈش, ئېكىسپورتى, كاتتالىق, قىرغىنچىلىق, چايناش, ئېغىزۇش يېمەكلىكلىرىنىڭ مېخانىكىلىق مۈلكى ۋە ساغلاملىقىنى ئومۇميۈزلۈك ئەكىرىشنى تىزىشقا ئىقتىدارلىق دەلىللىەلەيدۇ. 2.3-رەسىم HPMC قوشۇشنىڭ ئۈنۈمىنى كۆرسىتىپ بېرىدۇ, HPMC قوشۇشنىڭ ئۈنۈمىنى كۆرسىتىپ بېرىدۇ ۋە ھورلانغان بولكىنىڭ قاتتىقلىقى توغرىسىدىكى ئۈنۈملەرنى كۆرسىتىپ بېرىدۇ. نەتىجىدە كۆرسىتىلىشچە, HPMC دىن ئېشىپ كەتمەي, HPMC دىن ئېشىپ كەتتى, ھورلار كۆپ ھەسەتخورلۇق تەس. 355.555 ± 246.55 (قۇرۇق ئەۋرىشكى) دىن 310.44 ± 20.06 ± 20.06 ± 12.29 G (215.29 G (% 2 hpmc قوشۇلدى). بۇ ھورلانغان ناننىڭ كونكرېت مىقدارىنىڭ ئېشىشىغا مۇناسىۋەتلىك بولۇشى مۇمكىن. ئۇنىڭدىن باشقا, 24-رەسىمدىن قارىغاندا كۆرۈنىدىغان يۇقىرىلاردا, HPMC قوشۇلغان ئۆسۈش سوممىسىنىڭ كۆپىيىشىدە, يېڭى خېمىردىن ياسالغان پارنىسىيە% 0.968 (قۇرۇقلۇق) ئايرىم-ئايرىم ھالدا 0.96 (قۇرۇقلۇق). .02020 ± 0.004 (% 0.54 (% 1.006 ± 0.06 (% 1.00) ۋە 1.176 ± 0.03 (% 2.003 ±). پارنىش ۋە سالامەتلىكىنىڭ ئۆزگىرىشى HPMC نىڭ قوشۇلۇشى HPMC نىڭ نۇقسانسىز بولكىنى ئۆستۈرىدىكەن. بۇ rosjas, بېۋايتې دېگۈچ (2001] [95] [95] [95] [95] [95] [95] [95] [95] [95] [95] [95] [95] [95] [95] [onsms] [HPMC] [HPMC] [HPMC] [HPMC] دىن بىردەك, يەنى HPMC] دىن بىردەكلا كۆرۈنەرلىك تۆۋەنلىتىدۇ.

2-رەسىم HPMC قوشۇشنىڭ ئالدىنى ئېلىش ۋە خەنزۇچە ھورلانغان بولقىشنىڭ قاتتىقلىقى

يەنە بىر تەرەپتىن, توڭلىتىلغان خېمىر, ئۇ خېلى توڭلىتىش ۋاقتىنى كەلتۈرۈپ چىقىرىدىغان توڭلىمە ساقلاش ۋاقتى كۆرۈنەرلىك جاپالىق (0.0.05), ئېلفورختلىق يۈز بەرگەندە كۆرۈنەرلىك (p <0.05). قانداقلا بولمىسۇن, توڭلىتىلغان خېۋەنىڭ ھورلۇق ھەيڭى HPMC نىڭ HPMN نىڭ تەسلىكى 358.267 ± 42.167 ± 47.167 ± 37.15.01 دىن 1092.018 دىن 1092.014

توڭلىتىلغان خېمىرى توڭلغان پار, ياسالغان پار,% HPMC بىلەن% 2 hpmc دىن ئېشىپ كەتتى 208.233 ± 15.566 g (توڭلىتىلغان ساقلاش 0 كۈن) دىن 564.848 ± 60 كۈنلۈك (توڭلىتىلغان ساقلاش 60 كۈن). HPMC قوشۇلۇشىدىكى 24-رەسىم ۋە ئېلخەتكە تەڭشەڭنىڭ باھانى چۈشۈشتىن بۇرۇنقى خېمىرتۇرۇچنىڭ تەسىرىدىن 0.968 (0 مىليوندىن تۆۋەن نان) دىن 0.689 ± 0.022 (60-يىلغا بارغاندا, 20.022) % HPMC بىلەن توڭلىتىلغان ھورلانغان پاركۇسلارنىڭ ئېلاستىنىڭ ئاستا-ئاستا ئېغىشى 1.176 ± 0.003 دىن تۆۋەنلىدى (0.962 ± 0.003 (60 كۈنگە توڭدى). ئېنىقكى, توڭلىتىلغان ساقلاش مۇددىتى ئىچىدە توڭلىتىلغان خېمىرنىڭ ئۆزگىرىشى بىلەن تۆۋەنلەيدۇ. بۇ خىلتىكى HPMC نىڭ خەۋىرىگە قارىغاندا, HPMC نىڭ خەۋىرى: HPMC نىڭ كەمچىلىكى بىر ناننىڭ سۈپىتىنى ئۈنۈملۈك ياخشىلاپ چىقالايدۇ. ئۇنىڭدىن باشقا, 2.5 جەدۋەل HPMC دىن باشقا, باشقا تېكىستلىك بولكىنىڭ توڭلىتىلغان ساقلاش ۋاقتى توغرىسىدىكى ئېھتىياجنى تۆۋەنلىتىدۇ. ) كۆرۈنەرلىك ئۆزگىرىش يوق (P> 0.05); قانداقلا بولمىسۇن, توڭلىتىشنىڭ قانچە كۈنى, HPMC دىن ئۆسۈشى, سوۋۇتۇش ۋە چايناش كۆرۈنەرلىك (p

يەنە بىر تەرەپتىن, يېقىشلىق ۋاقىتنى ئۇزارتىش ۋە ھاش يۈزلىنىش ۋە ئەسلىگە كەلتۈرۈش كۈچى كۆرۈنەرلىك تۆۋەنلىگەندىن كۆرۈنەرلىك. HPMC نى قوشماي تۇرۇپ, HPMC نى قوشماي تۇرۇپ, پورلانغان بولكا سەۋەبىدىن ياسالغان بۇ پارتلىغان نانلار) 0.49 + 0.06 g (توڭلىتىلغان ساقلاش كۈچى 0.04) 60 كۈن قالدى. قانداقلا بولمىسۇن, توڭلىتىلغان خېۋە توڭدىن ياسالغان پارستىن 2 ھەسسە ئېشىپ, ئۇستاز) 0.93 + 0.03 g (توڭلىتىش كۈچى 60 كۈن) تۆۋەنلەپ 0.27 + 0.01 (توڭلىتىلغان ساقلاش كۈچى 0.07 + 4.01 (توڭلىتىلغان ساقلاش كۈچى 60 كۈنگىچە تۆۋەنلىدى, بۇ ئەسلىگە كەلتۈرۈش كۈچى 0.27 + 9.01) دىن تۆۋەنلىدى. بۇنىڭدىن باشقا, پارنىكۈزلۈك ساقلاش ۋاقتىنى پەيدا قىلىپ, ھورلانغان ناننى كۆرۈنەرلىك ئاشۇرۇش بىلەن كۆرۈنەرلىك ئاشتى. بوياق HPMC نى قوشماي تۇرۇپ, پارتلىغان خېمىرى توپا تۈگىدى, 37-نومۇرلۇق. 24 (سۈزۈلگەن 0 كۈنلۈك ساقلاش) نىڭ باھاسى 1232.87 (توڭلاتقۇ ساقلاش), توڭلىتىلغان 135.76 + 83.94 + 83.95 (ئەتىگەنلىك قانداقلا بولمىسۇن, توڭلىتىلغان خېۋە توڭلىتىلغان خېۋە توڭلىتىلغان پارستىن% 2 hpmc يەنە% 2 hpmc يەنە% 2 hpmc يەنە% 20.62 + 1 1.84 + 1 1.84 دىن ئەلالاش. 96 + 45.58 (توڭلىتىش ۋاقتى 60 كۈنلۈك), تۇڭراقتا 200.21 + 10.21 (STARZEN ساقلاش ۋاقتى 404.26 (STAZNUGE CHARE 60 كۈن). بۇ ۋاقىتتا HPMC نىڭ قوشۇلۇشى توڭلىتىش ئارقىلىق كېلىپ چىققان پارتلاش خالتىرلىقىدىكى ئۆزگىرىشلەرنى ئۈنۈملۈك چەكلەش ئۈچۈن. ئۇنىڭدىن باشقا, مۇزلاپ كەتكەن ساقلاش بوشلۇقىدىن كېلىپ چىققان پارنىلىسلىك تۇراقلىق ناننىڭ ئۆزگىرىشى (قاراقچى ۋە ئولتۇرۇشنىڭ كۆپىيىشىگە ئوخشاش) ۋە ئەسلىگە كېلىشنىڭ تۆۋەنلىشىمۇ بولۇپ, پارتلانغان بولاقلىق كونكرېت ھەجىمىمۇ ئىچكى باغۋەن. شۇنداق قىلىپ, دۆتلىك خانلىقلار (retrypaltysion جەرياننى قوشۇش, توڭلىمە پەيدا بولۇش, توڭلىتىلغان خېمىر ۋە پىچاقنى پىششىقلاپ ئىشلەنگەن پارس قوليۇتى مۇكەممەللەشتۈرۈلىدۇ.

2.4 باب

Hydroyprowyl Methylullouse (HPMC) بىر خىل گىتروفىللىق كولول كولوئىد بولۇپ, ئاخىرقى خىل مەھسۇلات يەنىلا كەمچىل. بۇ تەتقىقاتنىڭ ئاساسلىق مەقسىتى توڭلىتىلغان خېفر ۋە پومشۇنلۇق خۇسۇسىيىتىنى ياخشىلاش رولىنى تەكشۈرۈشنىڭ ئۈنۈمى ياخشىلىنىشىنى, شۇڭا HPMC نىڭ نان ۋە جۇڭگو ئۇسلۇبىدىكى ئۇن مەھسۇلاتلىرى بىلەن HPMC نىڭ ئۈنۈمىنى تەمىنلەشكە ئىگە. نەتىجىدە كۆرسىتىلىشىچە, HPMC نىڭ خېفېرنىڭ قۇتقۇزۇش خاراكتېرلىك مۈلكىنى ياخشىلىيالايدۇ. VPMC نىڭ ۋاقتى% 2 بولسا, كونترول بالدىقىنىڭ% 2) سۈمۈرۈلۈشى% 58.10 كە ئۆرلەيدۇ. 2 مىنۇت 12.2 مىنۇت شۇنىڭ بىلەن بىر ۋاقىتتا, خېمىل شەكىللىك ۋاقىتنىڭ كونترول گۇرۇپپىسىدا 2.1 مىنۇتتىن تۆۋەنلىگەن .5 مىليونغا يەتتى. ئاجىز دەرىجىدىكى ئاجىز دەرىجىدىن 55 فۇدىن 18 فۇغىچە ئازايدى. بۇنىڭدىن باشقا, HPMC يەنە خېمىرنىڭ بىر رىغبەت خاسلىقىنى ئۆستۈردى. HPMC نىڭ كۆپىيىشىگە ئەگىشىپ, خېمىرنىڭ ئۇزارتى كۆرۈنەرلىك ئاشتى. كۆرۈنەرلىك ئازايتىلدى. بۇنىڭدىن باشقا, مۇزيېكتورنىڭ يۈز سۆزىدە ئۈزۈنۈش ۋاقتىدا, خېفرىي تور قۇرۇلمىسىنىڭ كۆپىيىشىنى تۆۋەنلىتىدۇ, ئۇ يەنە بىر تور قۇرۇلمىسىنىڭ يۈز بېرىلىكىنى قوغدايدۇ, خېمىر تورىنىڭ مۇقىملىقى, خېمىر تورى قۇرۇلمىسىنىڭ مۇقىملىقىنى ئىگىلەيدۇ. ئاخىرقى مەھسۇلاتنىڭ سۈپىتى كاپالەتلەندۈرۈلدى.

يەنە بىر تەرەپتىن, تەجرىبە نەتىجىسى, HPMC نىڭ قوشۇلغانلىقىنى كۆرسىتىپ بېرىدۇكى, توڭلىتىلغان خېمىرىدىن ياسالغان پارنىمۇ ياخشى كونترول قىلىش تەسىرى بار. UNFROZEFS ئۈچۈن, NPMC نىڭ نان ناننىڭ كونكرېت مىقدارىنى كۆپىيىپ, ئېلانىنىڭ توكىرىنى كۈچەيتتى, شۇنىڭ بىلەن بىر ۋاقىتتا ھورلانغان بولاقنىڭ قان ۋەز -لىقىنى ئاشكارىلىدى. ئۇنىڭدىن باشقا, HPMC نىڭ توڭلىتىلغان زەربەنىڭ سۈپىتىنى ئۇزارتىش سۈپىتى بىلەن سۇنۇپ كەتكەن يۇلتۇزلارنىڭ ناچارلىشىشىغا, يېپىشقاق بولۇش, كۋادرات ۋە ئەسلىگە كەلتۈرۈش كۈچىنىڭ ئېلەۋىسىنى تارقىتىدىكەن.

خۇلاسە دە, بۇ ۋاقىتتا Shamed Bl نى بىر تەرەپ قىلىش ۋە گۈللەندۈرۈشنىڭ تېخىمۇ ياخشى ساقلاشنى ۋە مۇكەممەللەشتۈرۈش ئۈنۈمى بار.

3-باب HPMC نىڭ يوپۇرماقلىق شارائىتتا بۇرمىلىنىش ۋە خۇسۇسىيەتكە ئۇچرىشىنىڭ تەسىرى

3.1 تونۇشتۇرۇش

بۇغداي گلۇتېن بۇغداي تېرىكتىكى ئەڭ كۆپلۈك ساقلاش ئاقسىللىقى, ئومۇمىي ئاقسىلنىڭ% 80 تىن كۆپرەكىنى ئىگىلىدى. زاپچاسلىرىنىڭ ئەمەلگە ئاشۇرۇشىغا سانلىق مىللەت بولسا, ئۇ گۇلۇنمىن (ئەلكاۋىدىن ھەل قىلغىلى بولىدۇ) ۋە گوللاندىيەدە ئېرىمەڭ (ئەلكالېننىڭ ھەل قىلىش چارىسى). ئېتانول ئېرىتمىسىدە). بۇنىڭ ئىچىدە مولېكۇلا ئېغىرلىقى (MW MW) 1x107jA غا ئوخشاش يۇقىرى. ھەمدە ئۇنىڭدا تارماقچىسى ۋە ئوكۇلمول خاراكتېرلىك دېلونى شەكىللەندۈرەلەيدۇ. گالىدىنىڭ مولېكۇلاسىنىڭ يېرىمىلا 1x104da, بۇ يەردە پەقەت بىرلا سۇلىق بار, بۇ يەردە مولېكۇلالارنى ئىچكى دېلەۋەت قىلالايدۇ [100]. خېفېت, سەھش, خېف (1 996) خېمىر (سەككىزىنچى) ئارىلىقتا تارقىتىش) ۋە ئاقسىل جەمئىيىتى (خېف تور قۇرۇلمىسىنىڭ شەكىللىنىشى). ئادەتتە يۆتكەلگەندە, گلۇۋىرنىي خېمىننىڭ زالىنىڭ سالامەتلىكچانلىقى ۋە قۇرۇلمىنىڭ كۈچلۈكلۈكىنى بەلگىلەيدۇ, شۇنىڭ بىلەن خېلى روھنىڭ سىڭىپلاش ۋە سۇيۇقلانىنى بەلگىلەيدۇ [102]. GLUD ئاقسىلنىڭ ياردىمىدە شەكىللەنگەن ۋە خېمىر دەرىخى, خېمىروناشلار, خېمىرەت, ئېكسكۋا پارلىمى ۋە سۇ سۈملىشىش قاتارلىقلارنى كۆرسىتىدۇ.

ئۇنىڭدىن باشقا, بىر ئوكياننىڭ ئارىلىقىنىڭ تۆۋەنلىشىگە ئەگىشىپ, يەككە ئۆلچەملىك تور قۇرۇلمىسىنىڭ شەكلىگە ئەگىشىپ, بىر تەرەپ قىلىش زايومىپىات (پىشروگېن زايومى قاتارلىق كەڭ زايوم ([103] [103] [103] [103] [103] [103]. گەرچە ئىككىنچى بومبىنىڭ ئېنېرگىيىسى

مىلتىق ۋە مۇقىملىق ئالەم زايوملاردىن ئاجىز, ئەمما ئۇلار گولۇننىڭ كېلىشىمىنى قوغداش مۇھىم رول ئوينايدۇ.

توڭلىتىلغان خېمۇز, توڭلىتىش شارائىتى, تىركىرىياتسىيەلىنىش ۋە قايتاخېتىش جەريانى) نىڭ جىسمانىي تور قۇرۇلمىسىنىڭ جىنىسلىق جەھەتتىن ئېكرانىنى كەلتۈرۈپ چىقىرىدۇ, ئۇنىڭ قۇرۇلمىقىدىكى پۈتۈن دېلونى ۋەيران قىلىدۇ, مىكروسكوپ ھالاك بولىدۇ. گلۇتېن ئاقسىلنىڭ قۇرۇلمىسى ۋە خۇسۇسىيىتىگە ماس كېلىدۇ [105'1061. خۇگو, et A1. (2012) گاڭگىراشنىڭ ئۇزاقلانغان ۋاقىتتىن, مولېكۇلالىق ئېغىرلىقى ۋە مولېكۇلا تۇغۇلدى, مولېكۇلالىق ساغلاملىق مىقدارى تۆۋەنلەپ كەتتى [107جدە ئۇ كىلۇت ئاقسىللىق قىسمەن ھوقۇقلۇقلىقى ئاشكارىلاندى. بۇنىڭدىن باشقا, گلۇتېن ئاقسىلنىڭ ئۆزگىرىشى ۋە تېرمودىنامىكىلىق خۇسۇسىيەتلىرى يېمېندىنامىيابلىق خۇسۇسىيەت ۋە مەھسۇلات سۈپىتىگە تەسىر كۆرسىتىدۇ. شۇڭلاشقا, مۇز تەڭشەش جەريانىدا, سۇ شىتاتىنىڭ ئۆزگىرىشىنى تەكشۈرۈشنىڭ ئالاھىدە مەنىسى) ئوخشىمىغان توڭلىماقتا ساقلاش ۋاقىت ئەھۋالى ئاستىدا.

سېللېلوزاتېنىڭ تۇرىئېل قېپىدا تىلغا ئېلىنغاندەك, Sydroyprollyl Methylcellupplel MethylcellulloseLyL Methylcellupplel MethylcelluppleL Methylcellupplel MethylcelluppleL Methylcellupplel MethylcelluppleL MethylcelluppleL MethylcelluloseLse (HPMCC) توڭلىتى توڭلىتىش بىر يىل ئوقۇشقا ئەمەس, ئۇنىڭ ھەرىكەت مېخانىزمىلىرىمۇ تۆۋەن.

شۇڭلاشقا, بۇ تەجرىبە مەقسىتىدە, تەتقىقات ئەندىزىسىنى ئۆلچەپ, HPUT قىزىل مېيىگە كىرىپ, HLuten ئاقىلانە ساقلاش ۋاقتىنى, تېرمودىنامىيبىي مال-مۈلۈك ۋە ئۇنىڭ فىزىكا تاياقلىق خاسلىقى, ئاندىن پۈتۈشكەن بىر تەرەپ قىلىش مۈلكى, ئاندىن HPMC مېخانىزمىنىڭ ئۆزگىرىشى ۋە HPMC مېخانىز مەسىلىسىنىڭ سەۋەبىنى كۆرسىتىپ, مۇناسىۋەتلىك مەسىلىلەرنى چۈشىنىشنى ئۆستتۇرىدۇ.

3.2 ماتېرىيال ۋە ئۇسۇل

3.2.1 تەجرىبە ماتېرىياللىرى

Gluten ئەنخۇي رۇي فۇ Xu Xu xu xu xuo co., ltd. HydroxyPripyL Mythylcellulose (HPMC بىلەن ئوخشاش) ئالدانكىن خىمىيىلىك داۋالاش چەكلىك شىركىتى

3.2.2 تەجرىبە زاۋۇتى

ئۈسكۈنە ئىسمى

بايقاش. R3 rheometer

Dsc. Q200 پەرقلىق سىكانىرلاش ئىسسىقلىق ئۆيى

PQ00 1 تۆۋەن ساھە NMR ئەسۋابى

722E سپېكتروتومېتىر

JSM. 6490LV تۇڭستاڭ Firefation سىكانېرلاش ئېلېكترونلۇق مىكروسكوپ

Hh رەقەملىك تۇراقلىق تېمپېراتۇرا سۇ مۇنچىسى

BC / BD. 272 مەبلەغ توڭلاتقۇ

Bcd. 201Lect توڭلاتقۇ

مەن. 5 Ultra-microyperronic تەڭپۇڭلۇقى

ئاپتوماتىك مىكروگېر ئوقۇرمەن

نىكوللېت 67 ياللۇغى ئارال قىلىنغان سپېكترومېرنى ئۆزگەرتىدۇ

Fd. 1b. 50 ۋاكۇئۇمنى توڭلىتىدۇ

KDC. 160 سائەت يۇقىرى سۈرئەتلىك توڭلاتقۇنىڭ مەركىزى

Thermo Fisher FC تولۇق دولقۇن ساياھىتىنى سايىلەش مىكروبېر ئوقۇرمەن

Pb. Model 10 ph meter

Myp ll. 2-ماگنىتلىق قوزغىتىش

Mx. S تىپىدىكى Eddy ھازىرقى تەۋرىنىش

SX2.40.10 مۇپكە يەتتى

KjelleteC TM 8400 ئاپتوماتىك كىيگەنلىك Vitrogen ئانالىزچىسى

ئىشلەپچىقارغۇچى

ئامېرىكا TA شىركىتى

ئامېرىكا TA شىركىتى

شاڭخەي Nifeht شىركىتى

شاڭخەي Specum CERMEMENTER CO., LTD.

ئەمچەكلەر ئېلېكترون مەھسۇلاتلىرى CO., LTD.

جىنتان جىنخېڭ گوۋاچېڭ تەجرىبە زاۋۇتى

چىڭداۋ Hier گۇرۇپپىسى

Hefei mei ling co., ltd.

Sartorius, گېرمانىيە

تېرمو بېلىقچى, ئامېرىكا

Thermo Nicklet, ئامېرىكا

بېيجىڭ بويۇم بوڭ تەجرىبە ئەسكىرى چەكلىك شىركىتى.

ئەنخۇي جوڭ كەي جياڭ جيياڭ ئىلمىي ئەسۋاب چەكلىك شىركىتى چەكلىك.

تېرمو بېلىقچى, ئامېرىكا

Freroris Grower

شاڭخەي Mei Ying Pu Carde Com, LTD.

SCALGEX, ئامېرىكا

خۇاڭتا ئۇ تېبفېڭ تېببىي ئۈسكۈنىلەر چەكلىك شىركىتى.

دانىش تاشقا

3.2.3 تەجرىبە قايتا-قايتا

سىناقتا ئىشلىتىلگەن بارلىق خىمىيىلىك ئىجارە ئالغۇچىلار ئانالىز دەرىخى ئىدى.

3.2.4 تەجرىبە ئۇسۇلى

3.2.4.1 گۋاتېننىڭ ئاساسىي تەركىبلىرىنى بەلگىلەش

GB 5009.5010, GB 50093.2010, GB 50094.2010, Gb / Tiiseniange in 5003tain78-81], ئاقلىما نەملىك, ئاشۇر ياكى ليامۇلىنىڭ ماددىلىرى ئايرىم-ئايرىم ھالدا بېكىتىلگەنلىكى ۋە نەتىجىدە نەتىجىدە رول ئوينايدۇ.

3.2.4.2 توڭلىتىلغان ھۆل گلۇتېن خېۋىي (گلۇتېن خېمىر)

ئېغىرلىقى 100 گرام گۋاتېن ماسسىسى. ئېلىپ ئاندىن ئېلىپ, ئۇنى يېڭى ساقلاش خوراز ئورنىتىڭ, ئۇنى يېڭى ساقلاش خوراز ئورنىتىڭ, ئاندىن ئۇنى يېڭى ساقلاش خوراز ئورنىتىڭ, ئاندىن ئۇنى 4-نومۇرلۇق .30 at. 48 ℃ .18 ℃ for مەلۇم مۇددەت (15 كۈن ۋە 60 كۈن). توڭلىتىلغان 0 كۈنلۈك ئەۋرىشكىسىنى ۋە باشقا ئىشلەپچىقىرىش قەدەملىرى ۋە توڭلىتىش قەدەملىرى ئۆزگەرمەيدۇ, شۇڭا% 0.5 نى ئۆزگەرمەيدۇ, شۇڭا ھۆل تەمرەت يېتىشتۈرۈش ئەۋرىشكىسىنى پەرقلەندۈرۈش ئۈچۈن HPMC قوشۇش.

3.2.4.3 ھۆل گۋاتېن ماسسىسىنىڭ رىلوتولوگىيە خۇلاسىسىنى بېكىتىش

مۇناسىپ مۇزلاپ مېڭىش ۋاقتى ئاخىرلاشقاندا, توڭلىتىلغان ھۆل گللۇېن ماسسىسىنى چىقىرىپ, ئۇنى 4 سائەتلىك قاتناش توڭلاتقۇغا قويۇڭ. ئاندىن ئۈلگە پۈتۈنلەي ئېرىلىپ, ئۆينىڭ تېجىنىكىدا چىڭ قويۇڭ (بۇ خىل يېقىشلىق يېكىل ماسسىنى تالۋاسنىمۇ تەكشۈرۈشنىڭ بىر قىسمى, 2.7.1 ۋە 2.9.1 ۋە 2.7.1 ۋە 2.9). ئېرىتىلگەن ھۆل گللۇت كۆلىمىنىڭ مەركىزى رايونىنىڭ ئەۋرىشكىسى (تەخمىنەن 2 گ) ئۈزۈلۈپ قالدى. ستاتىستىكا سۈپۈرۈلگەن) سىزىقلىق VISP) نى تۆۋەندىكىدەك قىلىپ, كونكرېت تەجرىبە پاراشوكى 40 مىلكە ئۈلگە بولۇپ, بۇ بوشلۇق 40 مىلكە تەڭشەلگەن بولۇپ, بۇ بوشلۇق 1000 MRN غا تەڭشەلگەن, جىددىيلىك سۈزۈش دائىرىسى% 0.01. 100%, چاستوتىسى 1 Hz غا تەڭشەلدى. ئاندىن ئەۋرىشكىنى ئۆزگەرتىتىلگەندىن كېيىن, 10 مىنۇت تۇرايلى, ئاندىن ھەرىكەتچان

چاستوغىلاش سۈپۈرۈلۈڭ, كونكرېت تەجرىبە پارامېتىرلىرى تۆۋەندىكىچە, كونكرېت سىناق پارامېتىرلىرى - ئۈزلۈكسىز% 0.5 لىك (LVR), چاستوغلىق سۈپۈرۈش دائىرىسى 0.1 HZ. 10 Hz, باشقا پارامېتىرلار جىددىيلىك سۈپۈرگەن پارامېتىرلار بىلەن ئوخشاش. Sharinging سانلىق مەلۇماتلىرى رامكا شەكلى ۋە 5 سانلىق مەلۇمات (كۆرسەتكۈچ) گە ئېرىشكەن, شۇڭا Encisea ساقلاشقا ئېرىشىش ئۈچۈن چاۋاقەگە ئېرىشىش ئۈچۈن خاتىرىلەنگەن, ساقلاش لايىھىلىگۈچىسى (G ') بېكىتكەندە. دىققەت قىلىشقا ئەرزىيدىغىنى شۇكى, ھەر قېتىم ئەۋرىشكە ھامىللار تەرىپىدىن قىستۇرۇلغاندىن كېيىن, ئارتۇق ئەۋرىشكە تىغ توغرا رەتكە بولىدۇ, بىر قەۋەت بىر قەۋەت مېۋىسى ئەۋرىشكە ئىشلىتىلىدۇ. زىيان. ھەر بىر ئەۋرىشكە ئۈچ قېتىم كۆپەيتىلدى.

3.2.4.4 تېرمېنسىيەلىك مۈلۈكنى بەلگىلەيدۇ

بوتكىنىڭ ئۇسۇلى بويىچە (2003) [1081, ئالاھىدە سۈزگۈچ بالونۇھى (DSC Q.200) ئىشلىتىلگەن, ئەۋرىشكىلەرنىڭ مۇناسىۋەتلىك تېرمودىنامىكىلىق خاسلىقىنى ئۆلچەپ كەتكەن.

.

ھۆل گلۇتېننىڭ 15 مىللىگىسى ئېغىرلىقى ئېغىر ۋە ئاليۇمىنغا كرېستكە مىخلاندى ۋە ئاليۇمىن (سۇيۇق ئەۋرىشكە ماس كېلىدۇ). بېكىشات تەرتىپى ۋە پارامېتىرلار تۆۋەندىكىچە: 5 مىنۇتتا تېمپېراتۇرا (N2 CL C) نىڭ باھاسى 25 كىلوگرام (N2) نى تۆۋەنلىتىڭلار, ئاخىرى 25 مىنۇتتا 25 كىلومىتىر كېلىدۇ, ئاخىرىدا پېچەت پېچەتلەنگەن ئالدامچىلىق ئىدى. سېتىشتا DSC ئەگرى سىزىق 200 رۇپىيە يۇمشاق دېتالىنى سىنۇس كۆرگەزمىنى ئايلىنىش ئانالىزىدىن 2008-يىلىنىڭ 0 ° C قاتارلىق تەھلىل قىلىنغان. مۇز خرۇستالنىڭ ئېرىتى كىرىستەسلىك (YU كۈنى). ئاندىن, يۇقۇملىنىدىغان سۇ مەزمۇنى (CFW) تۆۋەندىكى فورمۇلا تەرىپىدىن ھېسابلىنىدۇ [85-86]:

بۇنىڭ ئىچىدە ئۈچ, نەملىكنىڭ يوشۇرۇن ئايروپىلانىغا ۋەكىللىك قىلىدۇ, ئۇنىڭ قىممىتى 334 JI / g. MC ھۆل گۋاتېننىڭ ئومۇمىي نەملىكىنىڭ ئومۇمىي نەملىكى (GB 50093.2010.2010). 78]. ھەر بىر ئەۋرىشكە ئۈچ قېتىم كۆپەيتىلدى.

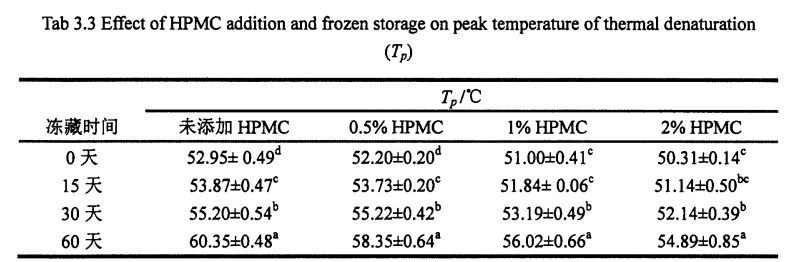

(2) بۇغداي يېتىشىنىڭ تېمپېراتۇرا چوققىسى (TP) نىڭ تېمپېراتۇرا (TP) تۈزۈلۈشى

توڭلاپ ساقلاش ئەۋرىتىنى توڭلاپ كېتىپ, ئۇنى يەنە ئېزىتىپ, ئۇنى قايتا تارتىپ, چىلۇپ ئاقسىل تالقىنىغا ئېرىشىش (بۇ قاتتىق پاراشوك ئۈلگىسىمۇ 2.8). بىر 10 مىللىم گلۇ گلۇكان ئاقسىل ئەۋرىشكىسى ئېغىرلاشتى ۋە ئاليۇمىنملىق كرېستكە مىخلانغان (قاتتىق ئەۋرىشكە ئۈچۈن) پېچەتلىدى. DSC ئۆلۈش پارامېتىرلىرى تۆۋەندىكىچە, 20 ~ CN قا پەقەت 20 پېچەتلەنگەن قۇرۇق ھالقىلارنى ئىشلىتىشنى ئىشلىتىش ۋە تەھلىل يۇمشاق دېتالىنى 2000 ئىشلىتىپ, ئېرىشكەن DSC ئەگرى سىزىقنى ئىشلىتىپ, بۇغداق يېشىۋىل ئاقسىلنىڭ نورمال چېكىگە ئېرىشىش (ھەئە) نىڭ چوققا چوڭىيىشىغا ئېرىشىش (ھەئە). ھەر بىر ئەۋرىشكە ئۈچ قېتىم كۆپەيتىلگەن.

3.2.4.5 بۇغداي گۇلفراتنىڭ مەزمۇنى (c)

ئەركىن سۇلف سەللە گۇرۇپپىسىنىڭ مەزمۇنى مەزمۇنى بولسا BeverIdg, باتارىيە ۋە راكاينىڭ ئۇسۇلىنى ئۇسۇلىنىڭ ئۇسۇلىغا ئاساسەن بېكىتىلگەنلىكىنى بەلگىلىدى. ئېغىرلىقى 40 مىللىمدىكى بۇغداي گولۋنېن ئاقسىل ئەۋرىشكىسى, ئۇنى قۇلۇپلاڭ, ياخشى سىلكىڭ ۋە ئۇنى 4 MLECELLL Sulfonate دا تارقاقلاشتۇرۇڭ

ناترىي ناترىي (). Tris-hydroxymethyl AminoMethane (tris). Glycine (gly). TGEINE (EDTA) بۇففېر (Tris) بۇففېر (Tris) b, 1.0 لىك GR لىق, 1% SH لار تەييارلانغان) يۇقىرىدىكى 10 مىنۇتتا, ھەر 10 مىنۇتتا چاپلانغان. ئاندىن, ئۇكىچە, ھەر 10 مىنۇتتا. 1 ° c ۋە 5000 × g 25 ℃ سۇ مۇنچىسىدا مەبلەغ سېلىشنى قوشۇش, 442 NM نى سۈمۈرۈپ, يۇقارقى تۆھپىلەر قۇرۇق كونترول ئىشلىتىلگەن. ئاخىرىدا, ھەقسىز sulfhydryl مەزمۇنى تۆۋەندىكى فورمۇلا بويىچە ھېسابلانغان:

بۇنىڭ ئىچىدە 73.53 بولسا يوقىتىش كوئاپاۋاسلىقى بارلار A سۈمۈرۈلۈش قىممىتى D سۇيۇق ھالەت ئامىلى (بۇ يەردە 1) G ئاقسىل مەركەزلىشىشى. ھەر بىر ئەۋرىشكە ئۈچ قېتىم كۆپەيتىلدى.

3.2.4.6 نى بەلگىلەش 1h مەن «2 ئارام ئېلىش ۋاقتى

Kontogiorgos غا ئاساسلانغاندا, گوفايس ۋە كاساسس 0.43 تال, رېئوننا چەمبىرىكى 18.169. تومۇر تەرتىپلىرى كارنى-purpol-meiboom-meiboom (100 دىن ئايرىم-ئايرىم ھالدا 13 ^ ۋە 25 ى ئىشلىتىلگەن ۋە تومۇر ئارىلىقى ئاخىرلىشىش مىقدارىنىڭ ئارىلىشىشىنى ئازايتىدۇ. بۇ سىناقتا, ئۇ O. 5 M S غا تەڭشەلدى. ھەر بىر گەيتىس 8 قېتىم سىكانىرنى سىكانىرلاپ, سىگنالنىڭ (SNR) نى ئاشۇرۇش ئۈچۈن سىگنالنىڭ (SNR) نى ئاشۇرۇش ئۈچۈن 8 قېتىم سىكانىرلىدى. ئارام ئېلىش ۋاقتى تۆۋەندىكى بىر قاتار تەڭلىمەدىن ئېرىشىدۇ:

بۇنىڭ ئىچىدە m تەكشۈرۈشتە ۋاقىت جەدۋىلىگە ئايلانغان بەلگە ئېقىشىنىڭ راك بەلگىسى بولغان روكنىسلىق سوممىسىنىڭ ئىقتىدارى. ياڭ) ئازادە يوللانما (D) بومبىسى (D) دېگۈدەك ئارام ئېلىش ۋاقتى (d) بىلەن مۇستەقىل ئۆزگىرىشچان.

كاشىلا كۆرۈلگەن ئانالىزى يۇمشاق دېتالىدىكى «ئۈزلۈكسىز ئۆزگىرىشتىن تاشقىرى ئۆزگەرتىشنى ئىشلىتىش, ھالقىلىق ھالقىما رەتسىزلىك ئەگرىسىگە ئېرىشىش ئۈچۈن ئېلىپ بېرىلغان. ھەر بىر ئەۋرىشكە ئۈچ قېتىم تەكرارلاندى

3.2.7, بۇغگۇر گولۋېن ئاقسىلنىڭ ئوتتۇرا قۇرۇلمىسى بەردى

بۇ تەجرىبىلەردە ئاۋازلىق يەككە بىر ئەكس ئەتتۈرىدىغان ئومۇمىي تەپەككۇرت (ATR) قوشۇمچە زاپچاسلىرى GLU. شىركىتىنىڭ ئىككىلەمگى قۇرۇلمىسى ۋە كادمىينىڭ داۋۇتنى تەكشۈرۈش سۈپىتىدە ئىشلىتىلگەن. ھەر ئىككى ئەۋرىشكە ۋە تەگلىك يىغىش, ھەر ئىككىسى 4 CM ~ ۋە سىكانېرلاش دائىرىسى 4000 CMQ-500 CM ~. ATR ماس كېلىدىغان ئالماسنىڭ يەر يۈزىدىكى ئاز مىقداردا ئاقلانغان ئاقسىل قاتتىق قۇۋۋەت, سىز سائەت 3 بۇرۇلۇپ, ئەۋرىشكەنىڭ ئىشەنچىسىدىن ئېشىپ كېتىشى ۋە ئاخىرى ۋارىسلىق گەپلەرنى ئېلىپ بېرىڭ, ئاخىرى سۇيىئىستېمال قىلىڭ. (سۈمۈرۈلۈش) ھوقۇق بېرىلگەن رازمېرلىق سپېكترى.

ئومونت يۇمشاق دېتالىنى ئىشلىتىپ تولۇق ۋارقىراپ-جارقىراپ-جارقىراپ كەتكەن سپېكترىغا ئېرىشكەن ماس 4.11 يۇمشاق دېتاللىرى ئاساسىي يېزىقچىلىق, فورمىنى رەتلەش (∥) 69 ياكى ئۇنىڭدىن يۇقىرى بولۇپ, ھەر بىر ئاقسىلنىڭ ئىككىنچى قۇرۇلمىسىغا ماس كېلىدىغان, ھەر بىر قوشنا IM'1) ۋە ھەر بىر پۈتۈن مەملىكەت قۇرۇلمىنىڭ بىر قەدەر ئومۇمىي سومما ھېسابلىنىدۇ. مىقدارى (%), يەنى يۇقىرى پەللىگە كۆتۈرۈلدى. ھەر بىر ئەۋرىشكى ئۈچۈن ئۈچ پاراللېل ئېلىپ بېرىلدى.

3.2.4 گىلەم ئاقسىللىقنىڭ Surface Hydrophouth نى بەلگىلەش

كاتو ۋە دىنۋا (1980] نىڭ ئۇسۇلىنىڭ دوكلاتىغا قارىغاندا, 1980], ناتفەين سۇلفسون كىلسىدلىت كىسلاتا (AND) ئەجەللىك تەكشۈرۈش سۈپىتىدە تارقىتىلغان. ئېغىرلىقى 100 مىللىمېتىر ئاقسىل قاتتىق قۇۋۋەت يۇمشاق دېتاڭ, ئۇنى 15 ئىنگلىز 32 فونكتا بۇفتىلدېلغا, ئاندىن 7000 rm لىق قوزغىدى, ئاندىن 7000 rm لار بىلەن ئارىلاشتۇرۇپ, كۆكرەك پارلاق ئۇسۇلنى ئۆلچەيدۇ. ئۇششاق-چۈشكۈندىن ھالەتنى ئاسناشقا ئورۇنلۇق, ئۇلار ئۆلچەش نەتىجىسىگە ئاساسەن, پارتلاش ئارقىلىق PBS ئۈچۈن PBS غا ئېلىنىدۇ, ئاقسىل مەركەزلىشىش 0 .02.5.5.c / MLG / MLG.

ھەر بىر GLADIT MAX ھەل قىلىش چارىسى (4 MML / L), ئاندىن تېزلا تەۋرىگەن يورۇقلۇققا يەتكەن. NM ھاياجانلانغان نۇر ۋە 484 دە بۇلغىما قويۇپ بېرىش نۇرى سۈپىتىدە. Surface Hydrophobication ناتوسىكلىتقا قارىتىلغان ئاقسىل مەرۋايىتلار بىلەن ماسلاشتۇرۇلغان. ھەر بىر ئەۋرىشكە كەم دېگەندە ئۈچ قېتىم تىترەپ كەتتى.

3.2.4 ئېلېكترون مىكروسكوپى كۆزىتىش

بەزى ئەۋرىشكە شىركىتى HPMC قوشماي, بەزى ئەۋرىشكە ئۈزۈلۈپ قالغاندىن كېيىن, بەزى ئەۋرىشكە ئۈزۈلۈپ قالدى, بۇ ئەۋرىشكە چىققۇدى, ئاندىن ئېلېكترونلۇق سىيدى سانتالانغان. مورفولوگىيىلىك كۆزىتىش ئېلىپ بېرىلدى. تېزلەش بېسىمى 20 KV غا تەڭشەلدى ۋە چوڭايتىش ۋاقتى 100 قېتىم بولدى.

3.2.4.10 سانلىق مەلۇمات بىر تەرەپ قىلىش

بارلىق مىنىستىرلىق 4 ئۆلچەملىك 4 خىل ئۇسۇل قائىدىسى بولۇپ, ئېلېكترون مىكروسكوپنى سىكاننېرلاشتىن باشقا كەم دېگەندە ئۈچ قېتىم تەكرارلاندى. 6.0 نى ئىشلىتىپ راكېتا سىزىش ۋە Spss 19.0 ئۈچۈن. ئۆزگىرىشچان ۋە دانكاننىڭ كۆپ دائىرە سىنىقىنى تەھلىل قىلىش, ئەھمىيىتى 0.05 ئىدى.

3. نەتىجە ۋە مۇنازىرە

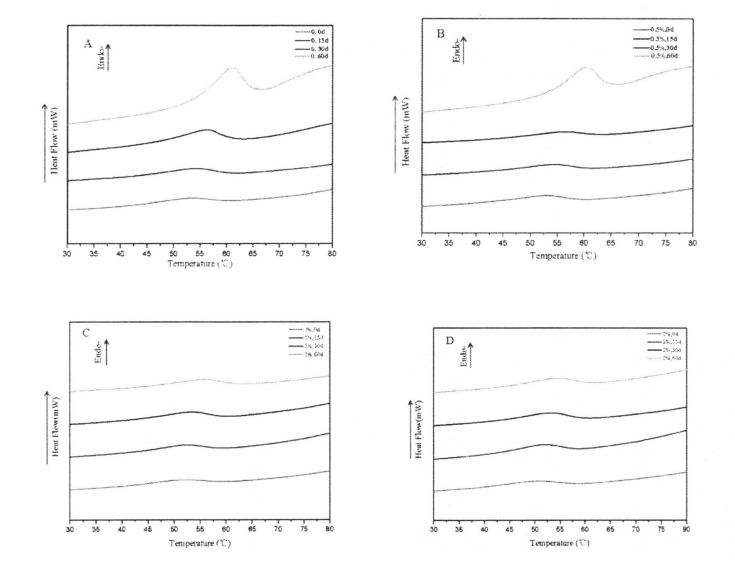

3.3.1 ھۆل گلۇتېن خۇلاسەنىڭ رىما خۇسۇسىيىسىدىكى HPMC قوشۇلۇش ۋاقتى ۋە مۇزلاش ۋاقتى

شىلويىلىك خۇسۇسىيەت يېمەكلىك ماتېرىياللىرىنىڭ قۇرۇلمىسى ۋە خاسلىقىنى ئەككاپ بېرىدىغان ۋە مەھسۇلات سۈپىتىنى مۆلچەرگە ۋە باھالاپ, مەھسۇلات سۈپىتىنى مۆلچەرگە ۋە باھالايدىغانلىقى ۋە باھالايدىغانلىقى ۋە باھالايدىغانلىقى ۋە مەھسۇلات سۈپىتى [113J. ھەممىمىزگە ئايان بولغىنىدەك, گللۇېن ئاقسىل خېمىرنى سۈمۈر بېرىدىغان ئاساسلىق ماتېرىيال تەركىب. 3.1-رەسىمدە كۆرسىتىلگەندەك, بارلىق ھۆل گىلاس سۈپال ئۇلارنىڭ خېمىرلاش ياكى ئالداش ھامىلىدارلىق شەكلىدە شەكىللەنگەن دۆلەت ئىچىدىكى دۆلەتتە تۇراقلىق ھالقىغان ENG Link نىڭ ئارقا كۆرۈنۈشى [114] شۇنىڭ بىلەن بىر ۋاقىتتا, گۇناھ ساتىدىغان مۇساپىلەر [114] يەنە بىر چىڭىتىش ۋاقتىنى ئۇزارتىدۇ. 115]. Gluten doughts% 0.5,% 0.5 تۆۋەنلەشنىڭ ئوخشىمىغان دەرىجىدە تۆۋەنلىشى (AM) ac. App 3.1). جىنسىي پەرقلەر (3.1, d رەسىم). بۇ توڭلىتىش جەريانىدىكى HPMC دا HPMC نىڭ ئۈچ ئۆلچەملىك تور قۇرۇلمىسى بۇزۇلغان بولۇپ, بۇلار كاسسىر مودا بولغان (2008) توڭلاتقۇچىنىڭ ئۈچ ئۆلچەملىك تور قۇرۇلمىسىنىڭ ئۈچ ئۆلچەملىك تور قۇرۇلمىسىنىڭ ئۈچ ئۆلچەملىك تور قۇرۇلمىسىنىڭ ئۈچ ئۆلچەملىك تور قۇرۇلمىسىنى بۇزغانلىقىنى كۆرسىتىپ بېرىدىغان. 2008

GLUMC LEAP نىڭ 311 ئۈنۈمى ۋە يېقىشلىق خېمىرنىڭ رىياسەتچىسى

ئەسكەرتىش: بۇنىڭ ئىچىدە HPMC نى قوشىسىز ھىلە سۇلياۋ ستۇدىك تەكشۈرۈش نەتىجىسى HPMC: b ئۈزلۈكسىز سىكانېرلاش نەتىجىسى HPMC نىڭ% 0.5 يۇقىرى پەللىگە كۆتۈرۈشى. C بولسا% 1 HPMC قوشۇشنىڭ چاستوتا سىكانېرلاش نەتىجىسى 2% HPMC ھۆل گلۇتېن ئوركانىيە چاستوتىسى قوشۇشنىڭ تەۋرىنىدۇ?

توڭلىتىش جەريانىدا, ھۆل گلۇتان مىللىتىدىكى نېرۋىر كۈچىنىڭ ئۆسۈشىگە ئەگىشىپ, مىلىزىمنىڭ ئۆسۈشىنىڭ ئۆسۈشى (چوڭ-كىچىكلىكى) نىڭ ئۆسۈشىگە ئەگىشىپ, مۇز كىرىستاللىرىنى يوقىتىدۇ. جىمجىت زەمبىرەك ۋە بىر ئاز خىمىيىلىك زايومنى بۇزۇش. قانداقلا بولمىسۇن, گۇرۇپپا توپنى سېلىشتۇرۇش ئارقىلىق كۆرسىتىلىشىچە, HPMC نىڭ قوشۇلۇشىنىڭ قارىشىچە, مۇز خرۇستال يولىنىڭ قۇرۇلۇشى ۋە كۈچىيىشىدە بولىدۇ, بۇ ئارقىلىق Glutuen تور قۇرۇلمىسىنىڭ پۈتۈنلۈكى ۋە كۈچى ۋە مەلۇم دائىرىدە, قوزغىتىش ئۈنۈمى HPMC نىڭ سانى بىلەن ئىجابىي مۇستەھكەملەندى.

3.3 HPMC قوشۇلۇشى ۋە توڭلاتقۇ نەملىك مىقدارى (CFW) ۋە ئىسسىقلىق دەرىجىسى ۋە ئىسسىقلىق ساقلاش ۋاقتى

3.3.2 HPMC قوشۇلۇشى ۋە توڭلاتقۇنىڭ نەملىك رايونى (CFW) دا توڭلاتقۇنىڭ مەزمۇنى (CFW) دا مۇزلۇق ساقلاش ۋاقتىنى قوزغىدى

مۇز كىرىستاللىرى مۇزلاش نۇقتىسىنىڭ ئاستىدىكى تېمپېراتۇرا ئۆتۈشى بىلەن شەكىللەنگەن باسقۇچلار قۇرۇلدى. شۇڭلاشقا, Setigable سۇنىڭ مەزمۇنى توڭلىتىلغان خېمىردىكى سان كىرىستاللارنىڭ سانى, چوڭلۇقى ۋە تارقىلىشىغا تەسىر كۆرسىتىدۇ. تەجرىبە نەتىجىسى (جەدۋەل 3.2) 02-جەدۋەلدىن باشلاپ مۇزنىڭ ساقلاش ۋاقتى بولۇپ, ھۆل تاۋ خەلىپىرلىق جۇڭگونىڭ پايچېكى ئۆرلەپ, قايسىسى باشقىلارنىڭ تەتقىقات نەتىجىلىرى بىلەن بىردەك [117.1ھۇش نەتىجىسى بولۇپمۇ 60 كۈن توڭلىتىلغان ساقلاشتىن كېيىنكى HPMC% 23.207.27, ئېشىش مىقدارى% 23.27 بولۇپ, ئېشىش مىقدارى% 23.27 بولۇپ,% 9.78 كە چۈشۈپ,% 19.59 ئاشقان. قانداقلا بولمىسۇن, ئەۋرىشكىلەرنىڭ% 20.5 بىلەن تولۇقلانغاندىن% 1.5, توڭلىتىش, Chnize نىڭ ئايرىم-ئايرىملىكى 20.07%, 63,% 15.96 ئاشتى, 16,% 15.96 ئاشتى, بۇلار ماتدا, A1 دە. (2008) قۇرۇق ئەۋرىشكىلەرگە سېلىشتۇرغاندا, قۇرۇق ئەۋرىشكىلەرگە سېلىشتۇرغاندا [119].

CFW نىڭ كۆپىيىشىدى ئاساسلىقى قايتۇرۇۋېلىش جەريانى ۋە گلۇېنت ئاقسىللىق تەدبىر قوللىنىلغاندىن كېيىن, سۇنىڭ تازىلىقسىز سۇدىن يېقىلغۇسىز سۇغا ئۆزگەرتىدۇ. بۇ ناشرېغلىق دۆلەتلەرنىڭ ئۆزگىرىشى مۇز كىرىستاللىرىنىڭ تور قۇرۇلمىسى بار بولۇپ, تور قۇرۇلمىسى (ئىشغار-تەرەت) ئاستا-ئاستا يىراقلاپ كەتتى. قانداقلا بولمىسۇن, ئەۋرىشكە بىلەن داغلىق Windows ۋە ئارقا مەھسۇلاتلارنىڭ مەلۇم مەزمۇنىنىڭ مۇھىم پەرقى كۆرسىتىلگەنلىكى ئېنىقكىچە, ئۇ يەردە مۇخبىرلارنىڭ يېغىشىڭ تور قۇرۇلمىسىغا ئازايتالايدىغانلىقىنى, ھەتتا مەھسۇلاتنىڭ سۈپىتىنى چەكلەيدۇ. ناچارلىشىش.

3.3.2.2 گىچە Gluten ئاقسىلنىڭ ئىسسىق بولمىغان مەزمۇنىدىكى HPMC ۋە مۇزلاش ۋاقتىنى

گوللۇېننىڭ كىرمەسلىك مۇقىملىقى زور بىر تەرەپ قىلىنغان پىشانىڭ شەكىللىنىشى ۋە مەھسۇلات سۈپىتىگە [211]. رەسىم 3.2 نىڭ تېمپېراتۇرىسى ۋە ئىسسىقلىق ئېقىمى (° C) بىلەن ئەڭ يۇقىرى بولغاندا DSGRISH نى كۆرسىتىدۇ. تەجرىبە نەتىجىسى (جەدۋەل 3.3) تىزىسىز سىيرىلما ئاقسىلنىڭ ئىسسىقلىقنىڭ دېزىنۇمنىڭ ئىسسىقلىق پەسلىدىكى ئىسسىقلىقنىڭ تېمپېراتۇرىسىنىڭ ئىسسىقلىقنى ئاشۇرۇۋېتىش تېمپېراتۇرىسىنىڭ ئۆيىدە XPMC نىڭ ئىسسىقلىق پەسكىچە بولغانلىقىنى بايقىدى, بۇ لېئون, ES A1 بىلەن بىردەك بولغانلىقىنى بايقىدى. (2003) ۋە كالھار, باراكار ۋە لاي سېگل (2013) 2013-يىلى) مۇشۇنىڭغا ئوخشاش كۆرگەزمە نەتىجىسىنى [2013 120M1. نوقۇل ئاقسىللىق ئۇنىۋېرسال ئاقماستىن% 0 لىك,% 0.4 ئۆسچە, ئىسسىقلىق مىقدارى% 0.40 to, 6.15 ℃, 5.02 ℃ ۋە 4.58 ℃, 5.02. ئېنىقكى, ئوخشاش مۇزلۇق ساقلاش ۋاقتى ئاستىدا, دېنىسى چوققىسىنىڭ تېمپېراتۇرىسىنىڭ ئۆسۈشى (N) HPMC دىن ئۆسۈشىگە ئەگىشىپ, HPMC دىن ئېشىپ كەتتى. بۇ يىغلاشنىڭ ئۆزگىرىشىدىن ماس كېلىدۇ. ئۇنىڭدىن باشقا, Unfrozen ئەۋرىشكى ئۈچۈن HPMC قوشۇلغان ئۆسۈم نىسبىتىگە ئوخشاش, N قىممەت دەرىجىسى توغرا تۆۋەنلەيدۇ. بۇ بەلكىم HPMC چوڭايتىلغان يەر يۈزى ۋە Gluth تېخىمۇ يېقىشلىق ۋە كەڭ كۆلەمدە بۇزۇلغان ۋە ئالدامچىلىق جىنايىتى بىلەن ئارىلىشىش سەۋەبىدىن بولۇشى مۇمكىن.

شۇنىڭدىن كېيىن: Myers ئوخشاش بىر ئىستوندىكى ئوخشىمىغان دەرىجىدىكى خەتكۈچ (p <0.05) كۆرۈنەرلىك پەرق (p <0.05) كۆرۈنەرلىك پەرقلەنگەن (1990-يىل ئاقسا قوزغاتقۇچ قوزغاتقۇچنىڭ تېخىمۇ ئارزۇسى توپلاشقانلىقى ۋە مولېكۇلنىڭ مۇددىئاسىغا قاتنىشىدىغانلىقىنى [1231] دەپ قارىدى. شۇڭلاشقا, گلۇتاندىكى گىدروپولوگىيەلىك گۇرۇپپىلار توڭلىتىشتىن ھالقىغان, ھەمدە HPMC نىڭ مولېكۇلا ئايلىقىنى ئۈنۈملۈك مۇقىملاپ قالالايدۇ.